|

By Gail Feinstein Forman

SAN DIEGO—Adam Gopnik, art historian and New Yorker magazine writer, captures the essence of the work of Jewish photographer, Richard Avedon, by describing them as “studies in human performance: how we prepare a face to face the world, and how the world shows itself in our faces.” SAN DIEGO—Adam Gopnik, art historian and New Yorker magazine writer, captures the essence of the work of Jewish photographer, Richard Avedon, by describing them as “studies in human performance: how we prepare a face to face the world, and how the world shows itself in our faces.”

Often considered America’s preeminent photographer, an extraordinarily rich compilation of Avedon’s work is now on display at The San Diego Museum of Art’s exhibit, “Portraits of Power.”

The exhibit showcases the breadth and depth of Avedon’s artistic talents as a photographic chronicler of America’s political and cultural landscape from the 1950's-2004, the year of his death.

Each grouping of photographs is from an original series of editorial projects that Avedon shot through the years on political themes. It ends with the last series,” Democracy,” he was shooting for The New Yorker when he died of a cerebral hemorrhage in June 2004.

Though Avedon is most widely known for his fashion photography and early work at Harper's Bazaar and Vogue, the stature and authority of his work—a minimalist black and white photographic portrait against a stark white studio background—gained him access to the celebrated and most powerful in the country.

Julia Marciari-Alexander, the curator of the “Portraits of Power” exhibition, remarked in an interview that, “This exhibition is really about how an artist can have an artistic engagement in a cultural, political and personal world.”

Aptly named “Portraits of Power,” the photos explore American power in many guises-who gets it, how they get it, and how they keep it.

The seemingly powerless are also represented and through the photographic image Avedon has created of them exert a power of their own.

For example, there are shots of Vietnam- era napalm victims that will stay with you long after you leave the museum, and soldiers from Iraq, holding weapons or standing with their family, reaching out to you asking to be remembered.

Included as well are formative portraits of a former slave, and two 1950’s grassroots civil rights workers, Jerome Smith and Isaac Reynolds

A thread that permeates the exhibit is how power is transformed over the course of time.

This is quite evident with the collection called “The Family,” a series put together for Rolling Stone in 1976 of America’s government elite, media moguls, lawyers, and labor leaders during the 1960’s and 1970’s. All these individuals shaped the historical and cultural expressions of the times.

Avedon represents these individuals in “line-up” form—all full body images set next to one another. Though many represent opposite sides of the political spectrum, this “line up view” can be read as a negative assertion itself. It serves to question the success of the politics of that time and what was really accomplished.

Many of these “culpable” individuals still remain in the public eye, such as Andrew Young, Jerry Brown, Donald Rumsfeld, and Henry Kissinger but the roles and influence they wielded before and have now has been fluid and changeable.

A photo of Tom Hayden also illustrates this well. Hayden first gained notoriety as part of a group of protesters, “the Chicago Seven,” who were clearly outside the political mainstream of the 1960’s.

They became well known for their disrupting tactics and eventual trial for conspiracy, and inciting to riot at the 1968 Democratic Convention. Avedon presents Hayden in a group photo of “the Chicago Seven.”

But Hayden’s life took a 360-degree turn and he later moved inside the political establishment and served in both the California State Assembly (1982-1992) and the State Senate (1992-2000).

This theme continues with an arresting photograph of Dr. Benjamin Spock in 1969 cradling his wife in an embrace as if she were an infant, a reminder of his 1946 blockbuster treatise on childrearing, Baby And Child.

Spock advocated a less stern approach to childrearing which was later criticized for being too permissive, negatively affecting the personalities of the entire generation of Baby Boomers, also known as “Spock babies.”

Later, in 1962 he was a political activist on the Committees for a Sane Nuclear Power, and later an outspoken leader against the Vietnam War. He even ran for president in 1972, far a field from his earlier days as a pediatrician.

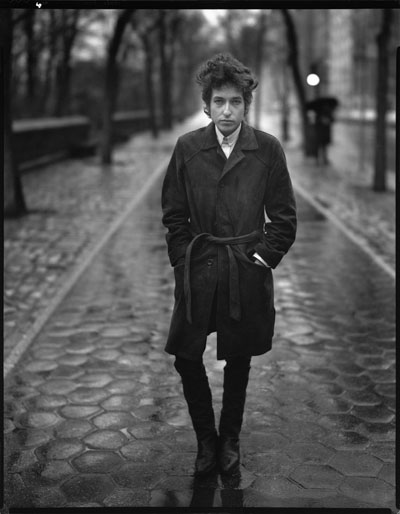

This can also be seen with the Pop icon Bob Dylan, composer of such American favorites such as Blowin' in the Wind and The Times They Are a-Changing' who also has a prominent place in the exhibit.

Avedon did a series of portraits of Dylan at different times in Dylan’s career; in 1963 at the very start of his career, 1965 as his popularity was rising and in 1997, when Dylan’s power was waning.

The exhibit contains the 1965 "The Central Park" photo and shows a weighted down Bob Dylan carrying the mantle of being the “Bard” of the nineteen sixties.

This Avedon portrait demonstrates what Mark Holborn, in an article in Granta magazine, calls “a study in the price of fame or the sheer weight of accelerated creativity.”

Another portrait that is striking in its prescience is that of Barack Obama taken when he was as keynote speaker at the 2004 Democratic Convention.

Avedon requested that this photo be the final portrait in any exhibit of “Democracy,” the last series he was working on and aimed at showing “a sense of the country” at this time.

Surprisingly, Avedon shot this photo in color and shows Obama in a thoughtful pose.

Several of the other shots in the “Democracy” series are also in color and show a heightened level of ethnic representation at the 2004 Democratic Convention that was lacking in earlier years.

The series also includes a moving portrait of a gay couple embracing their newly adopted child.

Avedon may have already sensed a new era in American democracy with an expansion of freedoms that elicited bright, patriotic hues for this series.

Throughout the exhibit, there is a palpable sense of the interactive nature each photo provokes. Each individual portrait is a montage of many elements that raises questions and invited a stream of emotions in the viewer

Avedon himself remarked that in each photograph “I have the person I am interested in and the thing that happens between us.”

Go to top of right column

| |

It is not surprising that Avedon’s first artistic prize was not for photography, but rather for poetry-for an inter-high school poetry contest at De Witt Clinton High School in the 1940’s.

Like a lyrical poem, the portraits are richly textured compositions cast in a particular rhythm, it seems, to be read out loud. Indeed, Avedon himself had referred to his photos as “performance pieces.”

One show-stopping example of this poetic vision is the portrait of Marian Anderson.

Avedon shot the photo in his studio in June 1955 to mark the auspicious occasion of Anderson’s Metropolitan Opera debut as their first black singer.

She was performing “Ulrica" in Giuseppe Verdi’s Un ballo in mascheraas (A Masked Ball) During the shoot, Avedon asked her to sing that same aria.

The resulting portrait is a study in poetic contrasts the way it expresses light and dark, hot and cool, open and closed. The windswept appearance of her hair enhances the sense of freedom and abandon the portrait projects.

One senses the courage Anderson required to move past years of racial discrimination in her career as well as her looking forward to the now-promising future.

The experience of each single photograph in this exhibition is sufficient to be an entire exhibit unto itself and reminded me of the following Zen story about the potential impact of a single work of art:

An American art dealer was invited to the home of a well-known Japanese painter to meet the artist and view some of his work for possible purchase.

The painter had offered tea to the art dealer and laid out one painting to look at while drinking tea.

The American art dealer quickly gulped down his tea and

became noticeably impatient. He had had enough tea drinking, had seen only one painting, and was waiting for more.

When he asked the painter to see the rest of the paintings, the artist replied, still quietly drinking his tea,

“You have time to see more than one painting?”

Richard Avedon was born in New York City in 1923 to Jacob Israel Avedon and Anna Polonsky, a sculptress. His father, a Russian-Jewish immigrant, had been brought up in a New York City Jewish orphanage and later founded Avedons of Fifth Ave – a successful women’s clothing store.

Richard grew up surrounded by fashion magazines and is quoted as saying he even used photos from the magazines to decorate his walls.

His father gave him a box camera when Richard was 9 years old. One of his first photos was of the musician and composer, Sergei Rachmaninoff, who coincidentally lived in the same apartment building as Avedon.

Avedon credits his appreciation of hard work and craft to hearing Rachmaninoff practice piano hour after hour every day.

He attended De Witt Clinton High School where he was co-editor of the school literary magazine with James Baldwin,with whom he later collaborated with on a book and photo series, Nothing Personal.

In 1942, he was drafted and began a stint in the photography branch of the Merchant Marine. His job was to take mug shots of the draftees for their ID card – grainy black and white photos on a stark white background, the start of his signature austere style.

After his military service ended in 1944, Avedon worked as fashion photographer for Bonwit Teller. It was here that he began to merge his interest in photography and poetry, as his shoots created artistic images reminiscent of a poem-nonlinear compositions with a story to tell.

To advance his photographic career, he practiced his photography by taking photos of his quite beautiful younger sister, Louise. Louise’s beauty and her early death at 42 in a mental hospital haunted Avedon all his life, and it contributed to the tragic sense of life, which permeated many of his portraits.

In the magazine Egoiste, in 1985 he said: "Louise's beauty was the event of our family and the destruction of her life. She was very, very beautiful. She was treated as if there was no one inside her perfect skin, as if she was simply her long throat, her deep brown eyes . . . All my first models - Dorian Leigh, Elise Daniels, Carmen, Marella Agnelli, Audrey Hepburn - were brunettes and had fine noses, long throats, oval faces. They were all memories of my sister."

In 1946, Avedon went to work at Harper’s Bazaar. Years later, he moved to Vogue and and became the first staff photographer at The New Yorker in 1992.

He received numerous honors in his long career, including being cited as one of the world’s top 10 photographers by Photography magazine early in his career in 1958.

He was described by those who knew him as a man of “impish intensity," “a notorious stickler for precision in his photographic technique." He loved his work and devoted his life to it. At times, the exacting nature of his work took an emotional toll on him.

"If each photograph steals a bit of the soul," he asked, "isn't it possible that I give up pieces of mine every time I take a picture?"

When you leave this sweeping and engaging Avedon exhibit, you, too will leave behind a piece of your soul.

The exhibit continues through September 6.

|