Volume 3, Number 197 |

'There's a Jewish story everywhere' |

Thursday-Saturday, October 22-34, 2009 Kasztner is the controversial figure in a new movie;

|

||||||

The arrangement was part of much broader Nazi negotiations that began in Slovakia with haredi Rabbi Michoel Ber Weissmandl and his cousin, Slovakian Zionist leader Gisi Fleischmann. The pair worked with the Zionists and the Vaad Hatzolah, an association of Orthodox Jews in New York, Nazi-occupied territory, and Switzerland, seeking to rescue Jews in Hitler’s Europe. But millions had to be raised from individuals and Jewish organizations for ransom. Not everyone could climb aboard that train, and there was a backlash of rage and resentment. First Person With the U.S. opening of the new documentary “Killing Kasztner” by Gaylen Ross, the controversy surrounding the negotiations for Jewish lives with Hitler’s deputies (Heinrich Himmler, Adolf Eichmann, Dieter Wisliceny, and Kurt Becher) is back on the front burner. For some, this is a very personal story involving Kasztner’s family and the families of the Kasztner survivors. For others, it is the story of political terrorism, described in full in the film by Kasztner’s murderer himself, Ze’ev Eckstein, a member of a radical-fringe right-wing group, who was recruited by Shin Bet to spy on the group and then joined them. He became part of a cabal to destroy Kasztner and perhaps, as a result, bring down the Israeli government. According to the film, Shmuel Tamir, the defense attorney for Gruenwald, had been a member of the Irgun, while Kasztner, covering for the Sachnut, did not want to admit that he wrote affidavits on its behalf for Kurt Becher and his cronies — the Nazi officials who looted Hungarian Jewry. The Sachnut and later the Israeli government under Ben-Gurion sought to recover Jewish goods and funds looted by the Nazis and didn’t want people to know they were in direct negotiations with war criminals. When asked about the Becher affidavit, Kasztner lied on the stand to protect the Sachnut, and thus became politically expendable. The Israelis also didn’t want to label “Jewish negotiators” as heroes. The Israeli idea of a hero, especially when training soldiers, was someone who would die, without talking, for the cause. Kasztner, who saved almost 20,000 Jews, more than anyone else during the Holocaust, was labeled a Nazi collaborator because he talked to Nazis. Even worse, said his enemies, he became one of them. As the film unfolds, as you listen and watch the face of Kasztner’s murderer, you cannot help concluding that in the Israeli mind at the time, Holocaust survivors were viewed as having been merely passive victims, told to keep quiet about their experiences, and expected to pick up arms and fight for the State. Until the early 1980s, when I joined the Arthur Goldberg Commission to examine the role of American Jews during the Holocaust (empowered by survivors and the City University of New York), I didn’t understand why some people hated Kasztner so much. Since not everyone could get on the train, the rumors that Gruenwald repeated as facts were spread everywhere: Kasztner kept the money; he should have stopped the deportations; he is responsible for the deaths of every Hungarian Jew not on the train. It was as if Hungarian Jewry never heard about Einzatsgruppen, Treblinka, Auschwitz, or the deportations from Slovakia next door. I asked my mother if that was true — that Hungarian Jewry didn’t know. And she told me that when she tried telling people what was happening just across their borders, they accused her of lying and trying to start a panic. Last summer, I interviewed Estie Blier, who was on the Kasztner Transport. She remembered an Auschwitz escapee who two years earlier described the Sonderkommando units in Auschwitz to Blier’s father, head of the bet din in Budapest. The man was dismissed as a lunatic. Others who tried to tell the truth were beaten in the synagogues. Hungarian Jewry didn’t want to know. My mother’s recollections are confirmed by a Hungarian survivor in “Killing Kasztner.” In mid-1944, my mother was sent to Budapest by her brother, the Munkascer rebbe, Baruch Rabinowicz, who was working on rescue with Jewish, Zionist, and Hungarian leaders. She was put in the care of Philip Freudiger, head of the Orthodox Jewish community in Budapest, who added 80 people — rabbis and their families — to the passengers on the train. That included my mother’s first cousin, the Satmar rebbe, Yoeli Teitelbaum, a rabid anti-Zionist. Reb Yoeli would later betray Kasztner when approached to be a character witness. He said that God had saved him, not Kasztner. My father, a vice president of the World Agudath Israel (the Agudah), told me before he died in 1982 that the Agudah had been deeply involved in the Vaad Hatzolah and helped arrange the ransom. So when I was on the Goldberg Commission, I approached Rabbi Moshe Kolodny, the Agudah archivist, who sent me to Prof. David Kranzler, a contributor to the commission’s report and an expert on the negotiations surrounding the train and other Orthodox rescue efforts. I learned that the Kasztner Transport was not something Kasztner did alone. The Sachnut, the Agudah, the international Vaads, Hungarian Jews, the U.S. government, American Jewish community leaders (who concentrated on creating a “homeland,” not rescuing European Jews), the Allies — dozens of high-powered people were involved in or knew about the “Blood for Trucks” deal, as Eichmann phrased it, that culminated in the Kasztner Transport. Kranzler’s commission document, “Orthodox Ends, Unorthodox Means: The Role of Agudath Israel and Vaad Hatzalah during the Holocaust,” shows how Slovakians Weissmandl and Fleischmann tried to save as many Jews as they could. The rabbi paid $50,000 to the Nazis in 1942 for 20,000 lives. Then he negotiated “The Europa Plan” with Himmler: $2 million for most of European Jewry. He enlisted Kasztner and the Hungarian Zionists to help. The Sachnut and most American-Jewish organizations turned down the deal. Then, in mid-1944, Weissmandl’s ad-hoc group spent six weeks pursuing Eichmann’s offer of a million Jews for 10,000 trucks, a deal “done in by circumstances,” according to Kranzler. Joel Brand, Kasztner’s negotiating partner and a Sachnut representative, left Hungary to find money for 10,000 trucks. The American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee, represented by Saly Mayer, refused to provide the needed funds because the trucks would be useful to the enemy. As ordered by the Sachnut, Brand went to Istanbul and ran into trouble when his Sachnut bosses did not provide backup. Then they ordered him to Aleppo, Syria, where the British arrested him because they did not want him to make deals with the Germans. That same spring, according to Kranzler, two escapees from Auschwitz, Rudolf Vrba and Alfred Wetzler, warned everyone that Auschwitz was being expanded in anticipation of Hungarian Jewry’s arrival and murder. They wrote a 36-page report, the “Auschwitz Protocols,” condensed by Weissmandl and sent to Jewish groups in Hungary and Switzerland. Kasztner received a copy while negotiating the truck deal with the Nazis.

|

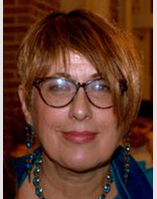

been deported. He wrote about “hopeless hopes”: how 12,000 Jews a day were being deported and it couldn’t be stopped; from that point on, only small numbers of Jewish lives could be negotiated, and that there were no Jews left in the provinces. Protests from the Red Cross and others “found no willing ears” and those were the “bitter and stark facts.” His colleagues, who wrote to U.S. government representatives in Switzerland, confirmed his observations. Another “Protocols” recipient was George Mantello, the Salvadoran consul-general in Switzerland who worked with British intelligence to condense the “Protocols” and get them to the media. Five days later, everyone knew what was happening to Hungarian Jewry. Even Pope Pius XII protested. Sweden’s Raoul Wallenberg was sent to Budapest to open safe houses, as was Carl Lutz of Switzerland, and, at last, the International Red Cross got involved. Months later, despite the Nazis, the regent, Miklòs Horthy, finally stopped the deportations on July 7, 1944. In the meantime, because of the publicity, the Nazis wanted to break off negotiations to release a half million Jews, but Kasztner convinced them to let a train leave carrying 750 people holding Palestine certificates (provided by the Sachnut). Among them were some members of Kasztner’s family, but not all — more than 100 were deported to Auschwitz. Kasztner also put other friends and relatives from his hometown of Kluj on the train. But money was needed and 150 very rich passengers (out of 1,684) paid huge sums to defray the cost of the cattle train, and the money went directly to the Gestapo. The rest paid nothing. In addition to Kasztner’s people and Freudiger’s people, as many as 450 inmates from a nearby labor camp climbed on board, and my mother remembers people getting off and on whenever the train stopped. But once the train was organized, according to Kranzler, Kasztner heard nothing from Switzerland. The Nazis refused to let the train leave Budapest until Weissmandl wrote them a note under a fictitious name informing them that 250 equally fictitious trucks were available in Switzerland. The Gestapo believed it. Only then was the Kasztner Transport allowed to leave Budapest on June 30, 1944, eventually arriving in Bergen-Belsen. The Americans warned the Sternbuchs they would be charged under the Trading With the Enemy Act, but they continued to plead and negotiate. As a result of their efforts, the first 315 hostages from the Kasztner Transport were released from Bergen-Belsen on August 21, 1944. Then McClelland insisted that Mayer replace Isaac Sternbuch in the negotiations. Small payments were then made to the Gestapo as Mayer stalled and Kasztner tried to ransom the rest of European Jewry. Kasztner convinced Mayer to fake a cable to the Gestapo that said SF 5,000,000 was available. As a result, in December 1944, the remaining 1,366 passengers, including my mother, were released, and according to Leland Harrison, an American diplomat in Switzerland, more than 17,000 others were held “on ice,” as Kranzler put it, in Austrian labor camps. When I saw Killing Kasztner, I knew about the negotiations. As a child, I don’t remember discussions of the devastating Kasztner trial in Israel or his assassination. I do remember hearing that he was murdered, supposedly by a crazed Hungarian survivor, and that when I told people my mother had been a passenger on the train, they made nasty cracks and derided Kasztner, as if he had been a one-man show. Last week, I met Kasztner’s granddaughter, Merav Michaeli, and it was like meeting a long-lost family member — there was a deep connection. After all, if not for her grandfather, I would not exist. Merav, a journalist, says it wasn’t the family’s idea to pursue the story. Gaylen Ross, the filmmaker, was fascinated by the story and shot her first footage at the Museum of Jewish Heritage in New York, during a Kasztner symposium. It shows the museum’s director, David Marwell, trying to control an unruly crowd. The result was Killing Kasztner, a film that tells the story of a murderer who comes face-to-face with the daughter and granddaughters of his victim. It is a heart-stopping, infuriating film, but Merav doesn’t seem to carry any of the rage that lies at the heart of the story. To her, the whole thing is a mystery. “The most amazing thing I realized from the movie,” she says, “was how Tamir [Gruenwald’s defense attorney] got hold of [the] Becher affidavit. It was in a box of papers given to him by the attorney general who brought the case in the first place. Why would the attorney general include such a damning piece of paper? I am sure that many things are waiting to be revealed.” I wonder out loud how it must have felt to meet Eckstein, as arranged for the film by Ross. How impossible it must have been for Merav, her sisters, and her mother to confront him. Merav says, “My mother wanted to meet with him at least 15 years ago, and he always refused. I felt as if my obligation was to be detached and angry at him. But I was in a coma as I sat there on the couch in my journalist mode, trying to be objective. He seems very intelligent and self-protective, and what happened and how he tells it seems to have been deeply thought through and processed. My ultimate impression is that he is not a bad person, but he ended up doing a terrible thing, and now seems trapped by it. “But I think my mother, who has a clean soul, connected with him. She really had good intentions, and wanted to meet him when he did not [want to meet her]. And when you ask about anger, I realize I was born into a situation where my mother carried the guilt forced on her by society. That guilt was passed on to me, and I had to prove what they said about Kasztner was a lie — for now he is guilty until proven innocent. They are angry because he did what they said could not be done. Our family’s victimization came from Israelis and perhaps, as women, our anger is inner-directed. I guess you can say in that way my mother is not a typical 2G [Second Generation].” Killing Kasztner took seven years to make, and when it started the family did not know Ross was going to focus on Eckstein. Then, when the movie came out, it was as if history had been rewritten. Most Israeli viewers were amazed and sympathetic to the family. During the course of the film, even Avner Shalev, director of Yad Vashem, “transformed himself,” as Merav describes it. At first a rejectionist, he later accepted the Kasztner archives and reintroduced his story to the public. Says Merav: “The family was truly grateful when Yad Vashem had an official showing this past Yom HaShoah. It means things are finally starting to change.” The woman who made the film In the film, she brings the family and Kasztner’s murderer together. What ensues is an engrossing, fascinating encounter, but the filmmaker doesn’t choose between them. She lets the viewers decide if Kasztner was a hero or villain. She compares him to an inkblot. Ross said, in an interview on Monday, “People put on him what they feel. First and foremost, there is the guilt felt by the survivors for having lived while others died and then there are the moral questions of dealing with the Nazis and of buying Jewish lives for cash.” She added that “Jews questioned the motives of other Jews, forgetting that the Holocaust was a crime against humanity perpetrated by the Nazis, not Jews.” Later Eichmann slandered Kasztner at his own trial, and what Ross and others find astonishing is that people would rather believe a war criminal and killer like Eichmann instead of Kasztner, who tried to save Jews.

|

< Back to the top • Return to Main Page

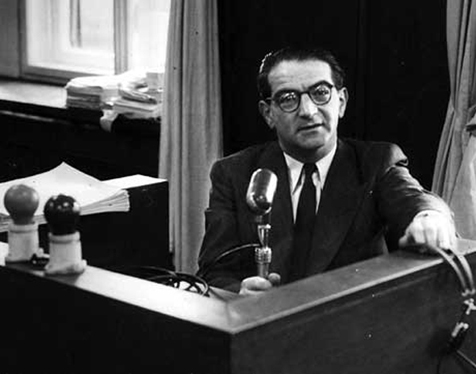

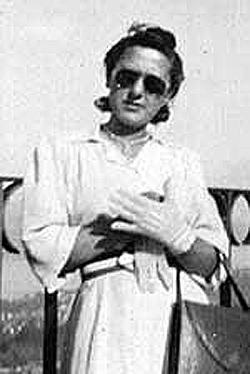

NEW MILFORD, N.J. —Until a few years ago, when people asked me about my Holocaust survivor parents, I would say that my mother, Peska Friedman, survived as a footnote in history. She was a Polish escapee from the Warsaw Ghetto who managed to get on a Hungarian train known as the Kasztner Transport. Named for Reszó/ Rudolph/ Israel Kasztner, the Hungarian Zionist leader and liaison to the Jewish Agency (the Sachnut), the train left Nazi territory — Budapest — in June 1944 for freedom in Palestine, via Switzerland. It was hardly an uneventful trip. Most of the passengers were held hostage in Bergen-Belsen for six months before they were released near St. Gallen, Switzerland. In the end, 1,684 people were saved, and most historians agree that the negotiations landed approximately 18,000 others in labor camps in Austria — where they were held as potential bargaining chips with the Allies instead of being deported to Auschwitz.

NEW MILFORD, N.J. —Until a few years ago, when people asked me about my Holocaust survivor parents, I would say that my mother, Peska Friedman, survived as a footnote in history. She was a Polish escapee from the Warsaw Ghetto who managed to get on a Hungarian train known as the Kasztner Transport. Named for Reszó/ Rudolph/ Israel Kasztner, the Hungarian Zionist leader and liaison to the Jewish Agency (the Sachnut), the train left Nazi territory — Budapest — in June 1944 for freedom in Palestine, via Switzerland. It was hardly an uneventful trip. Most of the passengers were held hostage in Bergen-Belsen for six months before they were released near St. Gallen, Switzerland. In the end, 1,684 people were saved, and most historians agree that the negotiations landed approximately 18,000 others in labor camps in Austria — where they were held as potential bargaining chips with the Allies instead of being deported to Auschwitz.