|

By Donald H. Harrison

LA JOLLA, Calif.—Sometimes facing your fears can pay dividends.

Mystery writer Faye Kellerman, an Orthodox Jew, not only never wanted to go to

Germany, but like her father she avoided all things German. She gave the labels

of food products double scrutiny. First she'd check the hechscher,

then she'd check what country the product was imported from. If it were from

Germany, it would go back onto the shelf.. Of course, she wouldn't set

foot in a Volkswagen dealership.

On the other hand, Germans loved Faye Kellerman. They enthusiastically

purchased her novels featuring Los Angeles Police Lieutenant Peter Decker and

his wife Rina Lazarus. They wanted her to come to Germany on a book

tour. Moreover, Kellerman's agent really wanted her to go to

Germany. So at last she relented, flying first to London's Heathrow

Airport to catch a connecting flight to Berlin. Sitting in the lounge,

waiting for her flight, she realized that all the people around her

were speaking German.

"I

became very nervous," she recalled to an audience Thursday

evening, March 23, at the Lawrence Family Jewish Community Center, where she was

interviewed on stage by Julie Potiker, an underwriter of the Distinguished

Authors Series. She said she began to wonder whether she would pass—would

the Germans look at her and think that she was Aryan or know that she was a

Jew? Her sense of paranoia did not decrease when she arrived at her hotel,

parted the window curtain and found herself looking at the Brandenburg Gate, a

symbol of Nazi Germany if ever there were one. "I

became very nervous," she recalled to an audience Thursday

evening, March 23, at the Lawrence Family Jewish Community Center, where she was

interviewed on stage by Julie Potiker, an underwriter of the Distinguished

Authors Series. She said she began to wonder whether she would pass—would

the Germans look at her and think that she was Aryan or know that she was a

Jew? Her sense of paranoia did not decrease when she arrived at her hotel,

parted the window curtain and found herself looking at the Brandenburg Gate, a

symbol of Nazi Germany if ever there were one.

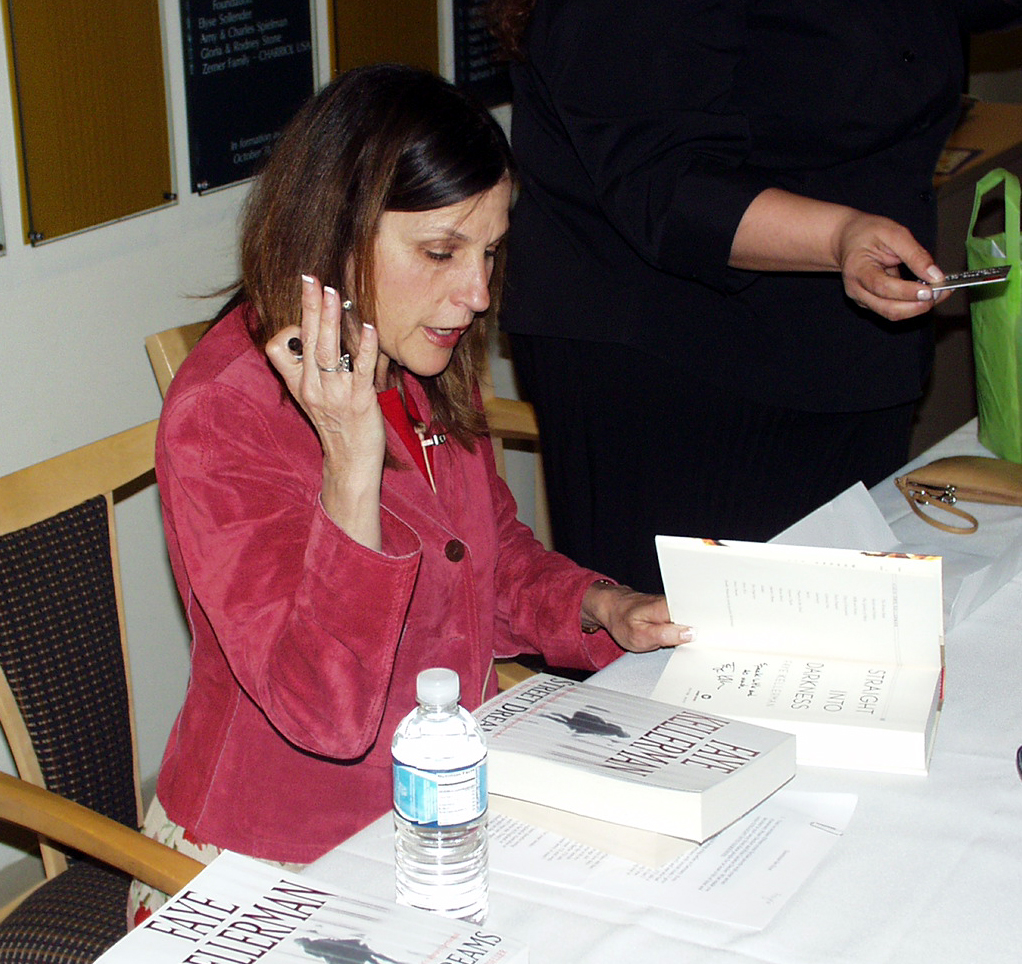

Faye Kellerman and Julie Potiker at Lawrence Family JCC

She had arrived in Berlin on a Thursday and her first speaking engagement was on

a Sunday. Her hosts took her on tour of Berlin's Jewish Museum

designed by Daniel Libeskind, the second-generation Holocaust Survivor more

recently chosen to design the new World Trade Center in New York. Then

came Shabbat and Kellerman said she attended services at a shul where the siddurim

were printed either in Hebrew and German or Hebrew and Russian. It was

an Ashkenazi service, she was familiar with all the prayer melodies, and

"it was like home."

Book talks in Germany were surreal. Kellerman would read in English,

then a German television actor—who reminded her of Tom Selleck playing the

role of Magnum P.I.—would read a translation in German. The audiences

were almost exclusively non-Jewish. "I felt Hitler would be rolling in his

grave."

And, everywhere she went, she saw memorials to Holocaust victims. A plaque

in front of a house saying here so-and-so and his family were arrested .

On this spot, Jews were assembled... Her feelings about the ever-present

reminders of the Holocaust were ambivalent. On one hand, it was good that

the Germans would never forget, but on the other hand "maybe it's not good

to make people feel guilty."

One of her eeriest moments in Germany was a visit to the Dachau

Concentration Camp. "You take the bus, and you get off where it

says 'Dachau'—How do you think that makes you feel?" she asked the

audience made up mostly of Jews from the San Diego area.

Dachau was a place like the one that her father never would talk about. An

immigrant to the United States at age 5, he served in the United States

Army during World War II. Because he spoke Yiddish, he was assigned as an

interpreter for the Jews who survived a concentration camp—Buchenwald,

his mystery writer daughter later found out. What he saw at

Buchenwald was a closed subject. In this way, American liberators, especially

the Jewish ones, and Holocaust survivors had a common bond. There were

things they wanted to forget, but couldn't.

During

question and answer sessions with her German audiences—or at the tables where

she signed books following her lectures—the people never brought up the issue

of the Holocaust, Kellerman said in response to a question from Potiker.

The fans asked about her mystery novels. But members of the German news

media always asked the question, albeit circumspectly. How do

you feel about being in Germany? The first time she heard the

question, Kellerman froze. That awkwardness "forced me to organize my

thoughts," she recalled. "I came up with an answer that

was somewhat satisfying." She told the reporters that "I don't

hold a grudge against the German people as I thought I might, but I feel like I

am walking on a bone yard." During

question and answer sessions with her German audiences—or at the tables where

she signed books following her lectures—the people never brought up the issue

of the Holocaust, Kellerman said in response to a question from Potiker.

The fans asked about her mystery novels. But members of the German news

media always asked the question, albeit circumspectly. How do

you feel about being in Germany? The first time she heard the

question, Kellerman froze. That awkwardness "forced me to organize my

thoughts," she recalled. "I came up with an answer that

was somewhat satisfying." She told the reporters that "I don't

hold a grudge against the German people as I thought I might, but I feel like I

am walking on a bone yard."

The idea for her latest novel, Straight Into Darkness, came to her while

she was on tour. Why not write a mystery novel set in Germany—not just

anywhere in Germany, but in Munich in the 1920s, when and where Hitler got his

start. She conceived a non-Jewish detective hero, Axel Berg, who was "very

precise, Teutonic." The case would come out of the period in

Germany after World War I when, she said, there were a lot of serial

killings and sexual killers.

As the plot lines of Kellerman's latest novel began to take shape, it became

clear that she would have to return to Germany to conduct the kind of research

necessary to demonstrate Axel Berg's familiarity with every aspect of

Munich. With the help of researchers, she found out the routes of the

street car lines, the gas lines, and the other minutiae that give a good

detective novel its air of verisimilitude. And she interviewed

people who had grown up during the time Hitler was coming to power, including

one member of the White Rose resistance group. From him, she learned that the

dictator had a habit of squeezing a roll into crumbs in his hand as he

gave his speeches—with a lackey sweeping up after him.

Germany was an intensely emotional experience for Kellerman, and her

return to the Peter Decker/ Rina Lazarus novels that made her famous was a

relief. Those two recurring characters have become so real to her, it is

as if they have lives of their own. There are times, she confided, when

she is writing a line, and "Peter will say to me, 'I wouldn't say something

like that, Kellerman.'"

Not so with her German detective hero, Axel Berg. It's unlikely that he too

someday will be able to protest, Das ist mich nicht, Frau Kellerman!

|