|

By Donald H. Harrison

Prof. Noel Pugach has been teaching American and Jewish history at the

University of New Mexico for nearly four decades, and is the first to admit that

any good lecturer needs to have a bit of the performer in him—or, dare I say

this about a fellow Jew—be something of a "ham." But Pugach

has raised his level of theatrics to an art, and appears around the

country in one-man portrayals of such figures in American history and

literature as President Harry S. Truman, Rabbi Isaac Mayer Wise, Lew Wallace and

John Steinbeck.

Unlike

actors who memorize scripts, Pugach draws on his own intensive research in

history, biography and literature to become that person on stage—first giving

a talk in which the subject tells about the high points of his life, and then

testing his wits by taking questions from the audience while remaining in

historical character. For people who love history, the combination is

compelling. Pugach packs a lot of information and anecdotes into his

lectures, and obviously enjoys sparring with audiences, who sometimes dispute

him. Unlike

actors who memorize scripts, Pugach draws on his own intensive research in

history, biography and literature to become that person on stage—first giving

a talk in which the subject tells about the high points of his life, and then

testing his wits by taking questions from the audience while remaining in

historical character. For people who love history, the combination is

compelling. Pugach packs a lot of information and anecdotes into his

lectures, and obviously enjoys sparring with audiences, who sometimes dispute

him.

For example, during one portrayal of Truman, a man in the audience gave

"Harry" hell about his account of his famous meeting at Wake Island

with General Douglas MacArthur. The man indignantly told the Truman on

stage that it wasn't true that MacArthur had kept him waiting, and he ought not

be telling such a story. The Truman character vigorously defended himself,

saying everyone who had been at Wake Island would back up his story.

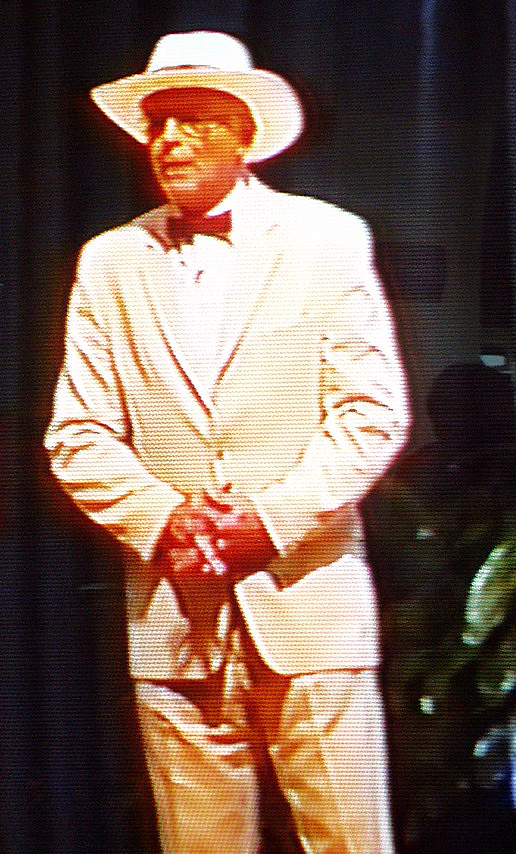

Pugach as Truman

At the end of his presentation, however, Pugach took off

his hat, and said he now wanted to step out of character. The questioner was

correct to doubt the veracity of Truman's account, he said, but that was the way

Truman told the story, and he, as Truman, had to stick to it. But as a

historian, he knew that there were other versions of the story.

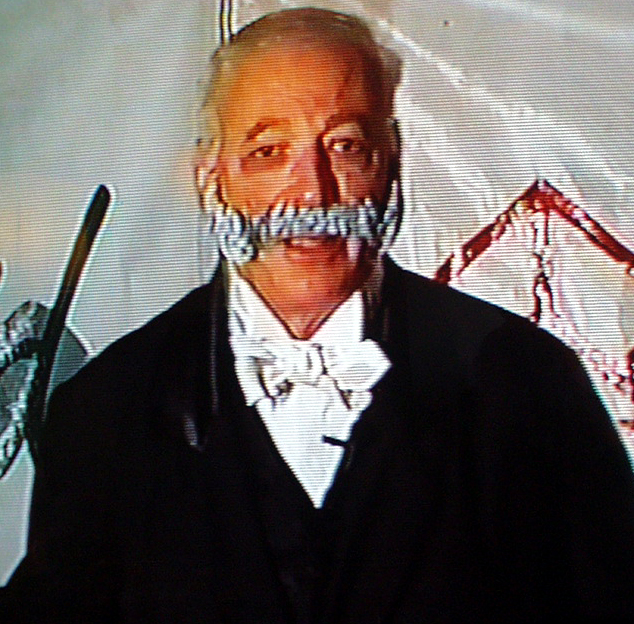

Viewing his portrayal of Rabbi Isaac Mayer Wise (1819-1900), I found

myself impressed by the depth of Pugach's research. There are far fewer

sources about Wise than there are about Truman, but the history

professor was able to bring this seminal figure in American Reform Judaism to

life. As Wise, he introduces himself as "an American of the Jewish

faith" and carefully sets out his positions on a number of controversies

that raged in 19th Century Judaism.

Wise

felt Orthodox Judaism lacked decorum in its prayer, and believed the cantors who

led Orthodox congregations in the United States to be "ignorant

men." As an American rabbi, he made it a point to shorten services and

to speak out on issues of the day. After being ousted from one pulpit in

Albany, he started another congregation in which he instituted "the family

pew," where men and women could sit at services together. He

predicted that women one day would preach from Jewish pulpits. He also

began holding Friday night services to provide an opportunity for Shabbat

worship for those who worked on Saturdays. Wise

felt Orthodox Judaism lacked decorum in its prayer, and believed the cantors who

led Orthodox congregations in the United States to be "ignorant

men." As an American rabbi, he made it a point to shorten services and

to speak out on issues of the day. After being ousted from one pulpit in

Albany, he started another congregation in which he instituted "the family

pew," where men and women could sit at services together. He

predicted that women one day would preach from Jewish pulpits. He also

began holding Friday night services to provide an opportunity for Shabbat

worship for those who worked on Saturdays.

Pugach as Rabbi Wise

At the same time as he was changing the established order of Jewish worship,

Wise also was making "many non-Jewish friends," including New York

state senators who elected him their chaplain, and President Zachary

Taylor, who made the "Jewish trivia" books by being the first President to greet a

rabbi at the White House.

Wise published a Jewish newspaper, American Israelite, both to spread his

views and to defend the Jewish community against attack. He was a strong

supporter of the doctrine of Separation of Church and State, and was a leader in

a campaign in Cincinnati, where he spent 45 years of his life, to resist having

Bible readings in the public schools. In addition, Wise was the main force

behind the creation of the Union of American Hebrew Congregations, the Hebrew

Union College, and the Central Conference of Rabbis. He also created an

American-style Jewish prayer book, Minhag America.

Today, some of his positions may seem surprising. He opposed Zionism

on the grounds that he believed Judaism should become an international religion

rather than a religion tied to one nation. He also was dismissive of

Darwin's Theory of Evolution in that it contradicted the notion that God created

man separately. On the biggest issue of the day, the abolition of slavery, he

declined to be drawn into the debate.

Pugach's portrayal of Harry S. Truman also treats some Jewish issues. He tells how when he was still a U.S. senator he criticized

President Franklin D. Roosevelt for not doing more to help Jews and other

victims of Hitler. He provides the background for the decision to cast the

U.S. vote at the United Nations in November 1947 for partition of

Palestine, and goes on to talk about all the pressure he was subjected to by

both sides concerning whether or not the United States should recognize the

Jewish State. On the one hand, Zionists including Rabbi Stephen

S. Wise (1874-1949) called for recognition; on the other hand were allied the

oil companies, Great Britain, the Joint Chiefs of Staff of the U.S. Military

service, and the U.S. State Department.

The Pugach Truman explained that the effects of the Holocaust weighed

heavily in the decision; he knew that the Jews who were living in

Displaced Persons Camps could never return to their former homes in

Europe. He dismissed the charge that he took a pro-Israel stand in order to win the

"Jewish vote," pointing out that in the subsequent successful 1948

presidential election against New York

Gov. Thomas Dewey, he lost the electoral votes of New York State—then, as now,

the state with the largest Jewish population.

Far more important than Jewish domestic votes, he said, was being able to woo

the Jews of Palestine to the American cause. He said he was quite concerned that

the Soviet Union would also try to recruit them as allies in the Cold War which

was then

reshaping the post World War II globe. At the time, he added, neither side

considered the Arabs to be reliable allies.

The presentation also told of Truman's friendship during World War I with Eddie

Jacobson, a Jew with whom he later opened a financially unsuccessful

haberdashery store in Kansas City, Missouri. The two men became life-long

friends, and although Pugach didn't mention the fact in the videotaped version

of his Truman performance that I saw, Jacobson would play an important role in

persuading Truman to discuss the Middle East with Chaim Weizmann, who later

became Israel's first president.

In a post-performance interview included with the

non-commercial Truman video, Pugach said he has five criteria for deciding which

historical subjects to portray. They should have made a mark in the world, there

should be plenty of information available about them; "I have to like

them;" there has to some humor in the story, and "they have to have

something to say."

While it is not a requirement for the subjects he selects, Pugach likes, when

possible, to be able to tell some Jewish story about the subject.

Wallace's famous fictional character, Judah Ben-Hur, was a Jew who furiously fought the

Roman overlords in the Holy Land, and who ultimately embraced the Christian

message of forgiveness. Wallace developed the famous story before he traveled to

the Middle East. According to Pugach, he was able to craft an amazingly accurate depiction of the

landscape of the Holy Land by interviewing travelers.

When Wallace did go to the Middle East, as U.S. minister to the Ottoman Empire,

he interceded in behalf of early Zionists who were seeking permission to live in

Palestine. He also spoke out against the persecution of Jews in

Romania.

Pugach weaves such Jewish tidbits into the overall Wallace narrative that deals

with other aspects of his career, including Wallace's support for the Mexican revolution of

Benito Juarez, his Civil War generalship for the Union, his service on the

tribunal in the war crimes trial of Confederate Capt. Henry Wirz (the

commander of the south's infamous Andersonville Prison); his encounter with the

outlaw Billy the Kid, and his term as governor of the New Mexico territory.

Likewise, Pugach found a bit of Jewish seasoning for his

portrayal of novelist John Steinbeck, telling briefly about the writer's trip to

Israel where he was shown around Masada by archaeologist Yigal Yadin. Steinbeck sent columns to Newsday on his impressions of the Holy Land.

With both American history and Jewish history as areas that Pugach knows well,

the professor finds himself attracted to stories in which his two interests converge. His

personal story is of an American Jewish boy with Orthodox grandparents, and

less observant parents—until a day that his mother agreed to let his grandmother

kasher the kitchen. Pugach attended the Brooklyn Talmudical Academy

one class behind future Harvard Law School Professor Alan Dershowitz, but resisted suggestions that he continue onto

Yeshiva University. Instead, Pugach did his undergraduate work at

Brooklyn College, and "got out of New York" to do his graduate studies

at the University of Wisconsin.

Approaching his 67th birthday, which will fall on Passover, Pugach is planning

to retire after this, his 38th year, as a professor at the University of New

Mexico. "Retirement!" he laughs, knowing that he will most

likely transfer his teaching from the university classroom to the stages of

auditoriums and Chautauqua tents across the country, where performers

impersonating historic figures—and even dialoguing and debating each

other—are a popular form of entertainment.

The performance as Rabbi

Isaac Mayer Wise that I saw had him being introduced by a character playing the

American author and philosopher Henry David Thoreau. At other times his

Truman has had lively debates with another impersonator's MacArthur.

Ever the teacher, Pugach also instructs Reform Jews of

Albuquerque's Congregation Albert—New Mexico's oldest Reform temple—

in studies of biblical texts. He recently completed a class on the

Book of Ruth. He utilized not only classical rabbinical scholarship to analyze

the story of Judaism's most famous convert, but also incorporated sources from

feminist literature and from archaeological expeditions to Moab, located in

modern-day Jordan. His own affiliation is with Chavurat HaMidbar, which

he describes as "one of the oldest independent Chavrot in the U.S..

"We have about 80 units—some single, more married, a couple of gays and

lesbians. We are traditionally oriented, (we use a traditional prayerbook) and

Zionist, but open, egalitarian, somewhat experimental,

democratic, totally lay led. We function though organized chaos. A very

interesting group. We were formed in 1973."

Pugach may be reached by telephone at the University of New

Mexico at 505-277-2701or via email, npugach@unm.edu.

.

|