|

By Donald H. Harrison

LA JOLLA, Calif.—In Tel Aviv, where a street is named for Zalman Shneour and a museum

collects memorabilia of his literary career along with that of his mentor Haim

Nahman Bialik, a gathering featuring a reading of Shneour's works

and the personal reminiscences of his son, Elie, probably could not have

occurred on such an intimate scale.

The man whose stories and poems in Yiddish and Hebrew made him a familiar figure in the

salons of Paris between the two World Wars—a man in whose home you might bump

into Pablo Picasso playing hide and seek with the Shneour children, or David Ben-Gurion

discussing the prospects of creating a Zionist state—simply would have been

too great a draw overseas to permit so privileged a gathering.

Elie Shneour, president and research director of Biosystems Research

Institute in the La Jolla area of San Diego, not only read his father's poetry and prose but also played for the

lucky 30 of us a privately-made, primitive recording of his father singing in

Yiddish and Russian. Additionally, those of us in the Astor Judaica

Library of the Lawrence Family Jewish Community Center on Monday evening, April

10, were treated to a sampling of Zalman Shneour's writing that

illustrated his unique perspective on Jewish history as well as his more

romantic side. Elie Shneour, president and research director of Biosystems Research

Institute in the La Jolla area of San Diego, not only read his father's poetry and prose but also played for the

lucky 30 of us a privately-made, primitive recording of his father singing in

Yiddish and Russian. Additionally, those of us in the Astor Judaica

Library of the Lawrence Family Jewish Community Center on Monday evening, April

10, were treated to a sampling of Zalman Shneour's writing that

illustrated his unique perspective on Jewish history as well as his more

romantic side.

The son, now 80, made the gathering even more intimate by

candidly discussing not only his father's brilliance but his flaws. Through his

word pictures, Elie Shneour enabled us to imagine how his father's

conversations with famous friends, coupled with his deep knowledge of a broad

range literature, sometimes would course together in black ink through Zalman Shneour's metal-tipped pen and be transformed into his small, precise, highly

focused handwriting. And we could appreciate that, when the Belorussian-born,

German-educated writer was

concentrating, how important it was for his children to keep the

house quiet, lest he come downstairs from his study, screaming, "Ah, I

can't work in this place!"

How far back do Zalman Shneour's literary excursions go into Jewish consciousness? In the Beginning, an essay excerpted by his son, provides a captivating

answer: Here are its opening paragraphs describing the void of the

biblical Bereshit

In the beginning God knew not that he was

God. Great Chaos reigned. An extraordinary confusion, devoid of hues, devoid

of time, of temperature, of limitations; a disorder that had never known the

nature of motion, or of sound, or what sort of a thing flame is. This

was no darkness—since darkness is but the opposite of light. This was no

dead stillness, for the greatest stillness is no more than opposite of motion,

of noise. This was no gelidity, no—for cold does not give a shading to

warmth. When it is cold one recalls warmth and yearns for it. This was a

nullity. A strange, eternal, all-prevailing dullness. A strange, great

desertlike obscurity, without a past, without a future, without an aim, and

without a meaning, and This reigned not because of anything but just because

it was. There was Chaos because there was Chaos.....

In The Testament of Don Henriques, a poem of a

Jew being burned to death in an auto da fé of the Spanish Inquisition, Zalman Shneour

imagined the Jewish martyr addressing his last words to his "ancient

brother of Galilee:"

...Do not place your trust in the Gentiles, Jesus!

Wandering through the centuries

I have learned their customs and mores,

I have compared their deeds with their words—

Your mercy is not to their taste:

It is as straw to the maw of the lion

Maloch still reigns in their churches

And the lust of the hunter still seethes in their blood...

The son's survey took us as well to Eastern Europe to pay

tribute to the hard-working Jewish peasants, in Where Are You Now?

...You were always redolent of timberland, axle-grease, rye flour and raw

hides. Even on the eve of the Sabbath, after the ritual bath, when you

struggled into your frayed, shrunken gabardines bought for the day of your

wedding; your bodies carried scents of your daily toil. You held your

prayer-books tenderly as if they were floundering yellow chicks; you held them

up while you swayed piously in prayer, with the same calloused, scarred hands

that heaved five-hundred-pound sacks and crates onto drays as if those sacks

were no heavier than skeins of cotton yarn...

In the voice of a biblical prophet, After the Warsaw Ghetto

assured Nazi Germany of the fate that awaited it at the end of World War II:

...No eye shall pity you,

Who shed so much blood.

You would have slain all the rest of us

If only you could.

What have you done with your heritage,

With your great past,

Sons of Beethoven and Goethe?

They would have shuddered at what you did,

Would have turned away from you, aghast.

What would Kant and Helmholtz have said?

They would have shrunk back,

You flung away their treasures of spirit,

And there is left only an empty sack...

The poet also wrote of love, and disappointment. In And There Are

Times, he mused:

..And there are times when dreams are vanities

Shadows of beauty, altars unto love,

And in the heart, the longings that arise—

All are beautiful—and all are lies....

As if to prove the thesis, the son read another of his father's poems, Forsaken:

Long past midnight I sit here

All alone with grief and fear,

And my heart is sore.

I hear the clock strike one,

One, one, one,

I have a husband but he has gone,

He loves me no more...

Elie Shneour also read for his friends Hal and

EileenWingard—the latter of whom introduced him at

the JCC event—A Whisper in Your Ear, one of their favorites of his

fathers' poems.

Red apples, green shadows,

Velvet grass, silk sky,

And with happy laughter

The stream rushing by

Come, my lovely angel

Plucking from the tree

You an apple, me an apple,

And a kiss for me...

How, it was asked during a question-and-answer session, had Zalman

Shneour gone about such writing? What was

his father's routine?

"He was a very disciplined writer," Elie responded. "He

would get up very early and would go down and have breakfast—eggs and coffee

and a few other things that he could eat—and then he would go up...to the

second floor where he had a bed and a study with a beautiful view and would do

nothing but ... work steadily until noon time.

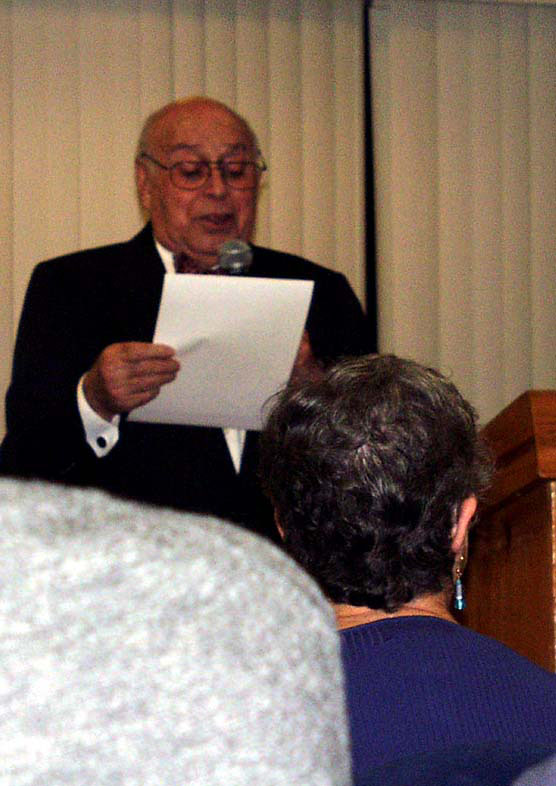

Elie Shneour, Eileen Wingard and Hal Wingard on April 10, 2006 "And that was his best

time. In the afternoon, he would usually go do other things. He would

walk, he would meet with people, he would go to Paris...where all the cognoscenti

would meet." Sometimes Elie would accompany his father to meet the famous painters

and writers who would gather in the salon of Gertrude Stein, and, being only a

boy, " I was

bored to death" because he would have to sit quietly while the

adults discussed politics and literature. The afternoon walks with his

father, however, were fun and quite memorable. "He was a very strong, very

earthy human being. When we wandered into the woods about a mile from us,

he would urinate in public, and said it is a wonderful feeling to urinate on the

leaves, and he enjoyed every aspect of living." His father had a way of

walking into the room—"he was tall, very handsome, women literally fell

at his feet, and I could tell you stories about his womanizing."

Despite the fact that Elie's mother, Salomea Landau, was a beautiful woman and a talented pianist,

his father...well... the son's voice trailed off as he gave his audience a look

that suggested such was simply the way his father was.

Elie admitted that it had not always been easy to be the son of a literary icon.

His mother once told him that he never would be as great as his father, and he

can recall once blurting to the poet, "I wish that I was the son of a

plumber." In a family where his father was a writer, his mother a

pianist, his sister, and his sister Renée Rebecca a dancer under the

professional name of Laura Toledo, Elie joked that he was the black sheep.

"I am a scientist!" Once, on a trip to Israel to give a

scientific lecture, after being introduced as Zalman Shneour son, he snapped:

"Dammit, I am not here as Zalman Shneour's son, I got here on my

own!"

When he was a boy in France, Elie's parents used to entertain dignitaries

at dinner parties. Conversation and wine flowed copiously, occasionally

causing Zalman the kind of restless night that resulted in him leaving his bed

for his writing table.

Often, Elie and his sister would be summoned to perform for the guests in the

salon—his sister dancing beautifully, and he playing the piano. "I was

lousy," he said, probably being unfair to himself. His credentials as

a musician are strong enough to have served as a rehearsal conductor for the Columbia

Orchestra.

Abba Eban and Ze'ev Jabotinsky were some of the Zionist leaders with whom his

father had close friendships and he often would debate religious philosophy

with the Lubavitcher Rebbe, Menachem Mendel Schneerson. The two men

had a bond: Zalman Shneour was a direct descendant of his namesake, Shneour

Zalman—the founder of the Chabad movement.

When Nazi Germany was swallowing France, Elie learned that his father had clay feet.

Zalman was utterly inert, unable to act in the face of

the threat, believing that "this is the 20th Century; nothing can happen to

France," Elie quoted his father as saying. "My mother said, 'no,

we have to go,' and if she hadn't done it I would not be speaking with you

today. We are the only survivors of our immediate family. Everyone

else ended up in the death chamber."

Elie, in fact, was captured and sent to the French concentration camp at Drancy,

but he escaped before the Germans could send him to Auschwitz. He said the

Nobel laureate Elie Wiesel once told him that his father, too, simply could not

believe anything bad would happen to the Jews of France. The Shneours made

it to safety through neighboring Spain, immigrating in 1941 to New York

City. There Zalman syndicated his

stories to Jewish newspapers all over the world. The Shneours obtained

property in Israel, which they visited occasionally. Zalman Shneour, 72, died

in 1959 after suffering a heart attack on a flight back to New York. His

body was returned to Israel where he is buried next to Bialik.

(The International copyrights on the literary works of Zalman Shneour quoted

above are secured by the Zalman Shneour Literary Trust, and are reprinted by

permission.)

|