|

By Donald H. Harrison

SAN DIEGO—My grandson, Shor Masori, came over to the house on his fifth

birthday on Thursday, April 20, to spend a few hours with me before the

family got together for a celebratory dinner. "Well, Shor, shall I read you

a book?" I inquired. "Yes," he said, although more and more

he likes to read them to me. I reached for one of our favorites

about Noah and the ark, and he made a face. "That was one we read

when I was four," he said. "I want a new one for a

five-year-old!"

Well, okay, I thought, the image of a sinking ark crossing

my mind. I went to a bookshelf and searched for children's books, and

found one that I had purchased in Marshall, Texas, when I was researching the

biography I wrote, Louis Rose: San Diego's First Jewish Settler and

Entrepreneur. Rose

had been one of those city fathers in the 19th century who actively

promoted the idea of San Diego becoming the West Coast terminus of a

transcontinental railroad running along our nation's southern border. On

March 3, 1871, Congress authorized the Texas and Pacific Railroad to acquire the

right of way and to begin construction between Marshall, Texas, which is

near the Texas-Louisiana state line, and San Diego, which, of course, is on a

wonderful bay on the Pacific Ocean.

Had

it not been for the rough topography lying to the east of San Diego—and a few

nationwide financial panics—San Diego, rather than Los Angeles, might have

been the terminus for a transcontinental route, and who knows how the history of

those two cities might have flip-flopped. The children's book I had

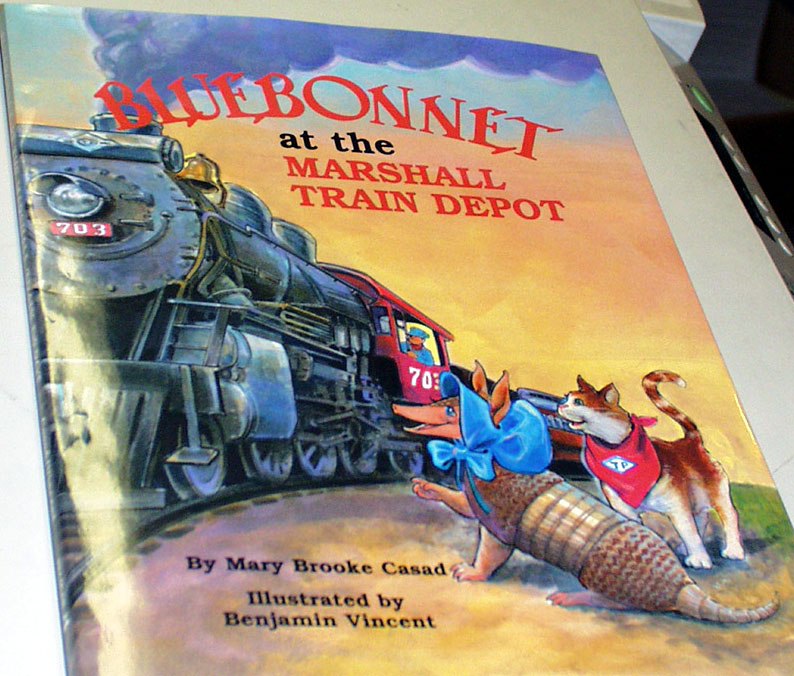

purchased and then had laid away for such a day as this was Bluebonnet at the

Marshall Train Depot by Mary Brooke Casad. Had

it not been for the rough topography lying to the east of San Diego—and a few

nationwide financial panics—San Diego, rather than Los Angeles, might have

been the terminus for a transcontinental route, and who knows how the history of

those two cities might have flip-flopped. The children's book I had

purchased and then had laid away for such a day as this was Bluebonnet at the

Marshall Train Depot by Mary Brooke Casad.

In the tale illustrated by Benjamin Vincent, an armadillo named Bluebonnet

wanders into Marshall and is met by TP the cat, who keeps watch over the Texas

& Pacific Depot. TP then takes Bluebonnet on a tour of the train

station, reciting more history than Shor really wanted to know, but the

armadillo seemed downright interested. Shor's interest quickened however when TP

and Bluebonnet decided to take a train ride together—neither of them having

ever taken one before. The two animal friends got on the train just in the nick

of time What happened next was left to the readers' imagination, perhaps

to be answered in a sequel.

As we read, Shor learned important words like "conductor,"

"locomotive," and "caboose." When we completed reading

the book, we went into his room—yes, he has his own room at his grandparents'

house, the same room that once belonged to his mother, Sandi

Masori—and retrieved his small train set. We pieced together the

circular railroad tracks and identified which car in the train set was the

caboose. We pushed the train around the tracks and made the sounds of

steam whistles together, probably driving grandma,

who was in a nearby room, close to distraction until it was time to get ready

for the birthday dinner.

On Friday, Shor came for another visit, and I had a surprise cooked up. We drove

to Balboa Park, where we went first to the 28,000-square-foot San Diego Model

Railroad Museum, located in the basement of the Casa de Balboa. I knew the

location well because on the same floor of this building are the archives of the

San Diego Historical Society, where I had spent so much time researching the

life of Rose.

Shor circled twice, or perhaps three times, through the various model train

exhibits including four major re-creations or conceptualizations: San Diego

& Arizona Eastern, Tehachapi Pass, Cabrillo Southwestern and

Pacific Desert Lines. The latter conceptualizes the California portion of

the route that Rose and other pioneers had envisioned as a stimulus for San

Diego's economic destiny. Occasionally, Shor climbed steps leading to

vantage points providing better views of the model railroads, but mostly he was

fascinated by the floor surrounding the exhibits on which had been laid

simulated tracks bearing the names of donors to the museum. He followed

the tracks determinedly, occasionally whoo-whoo-ing as he imagined himself to be

a runaway train.

Perhaps

we will return on other occasions to examine the details of the model railroad

more closely, this being simply an introductory visit. Leaving the museum, we

walked up the Prado, to Balboa's giant fig tree, had an ice cream, walked

through beautiful Spanish Village, to my next surprise for Shor—a ride on

Balboa Park's Miniature Railroad. The train was just leaving the station

as we arrived, and unlike Bluebonnet and TP, we did not just make it.

While I bought tickets for the next run, Shor could hardly contain his

excitement until the train completed its half-mile circuit about three minutes

later. Perhaps

we will return on other occasions to examine the details of the model railroad

more closely, this being simply an introductory visit. Leaving the museum, we

walked up the Prado, to Balboa's giant fig tree, had an ice cream, walked

through beautiful Spanish Village, to my next surprise for Shor—a ride on

Balboa Park's Miniature Railroad. The train was just leaving the station

as we arrived, and unlike Bluebonnet and TP, we did not just make it.

While I bought tickets for the next run, Shor could hardly contain his

excitement until the train completed its half-mile circuit about three minutes

later.

Shor took the seat right behind the engineer, and I took the seat right behind

him, holding his hand for safety. Away we went, whistle blowing, and I

don't think anything could have been better as far as Shor was concerned—but I

was wrong. The best part was when we went through a long tunnel and the

conductor blew the whistle again. I'll have to admit, the echo was

impressive.

We returned to the large fountain of Balboa Park where Shor

made a wish and tossed a penny, and then headed for our car. We talked

over our adventure as we drove home. "What kind of trip would you

rather go on, a train or an ark?" I asked Shor. He didn't hesitate

for a moment. "An ark!" he replied. "That way, I'd

meet Noah."

That's my grandson, I thought. I don't know if Shor got what he wished

for, but I certainly did!

|