|

By Donald H. Harrison

SAN DIEGO, Calif.—On a day when a federal district court

judge ruled that the City of San Diego must remove a large Christian cross from

public land atop Mount

Soledad, a rabbi and a priest who are nationally known theologians held a

dialogue at the University

of San Diego dealing with issues that the two religions confront.

The public meeting was held in the John B. Kroc Center for Peace and Justice,

named for the late philanthropic widow of Ray Kroc, the founder of the worldwide

McDonald's hamburger chain.

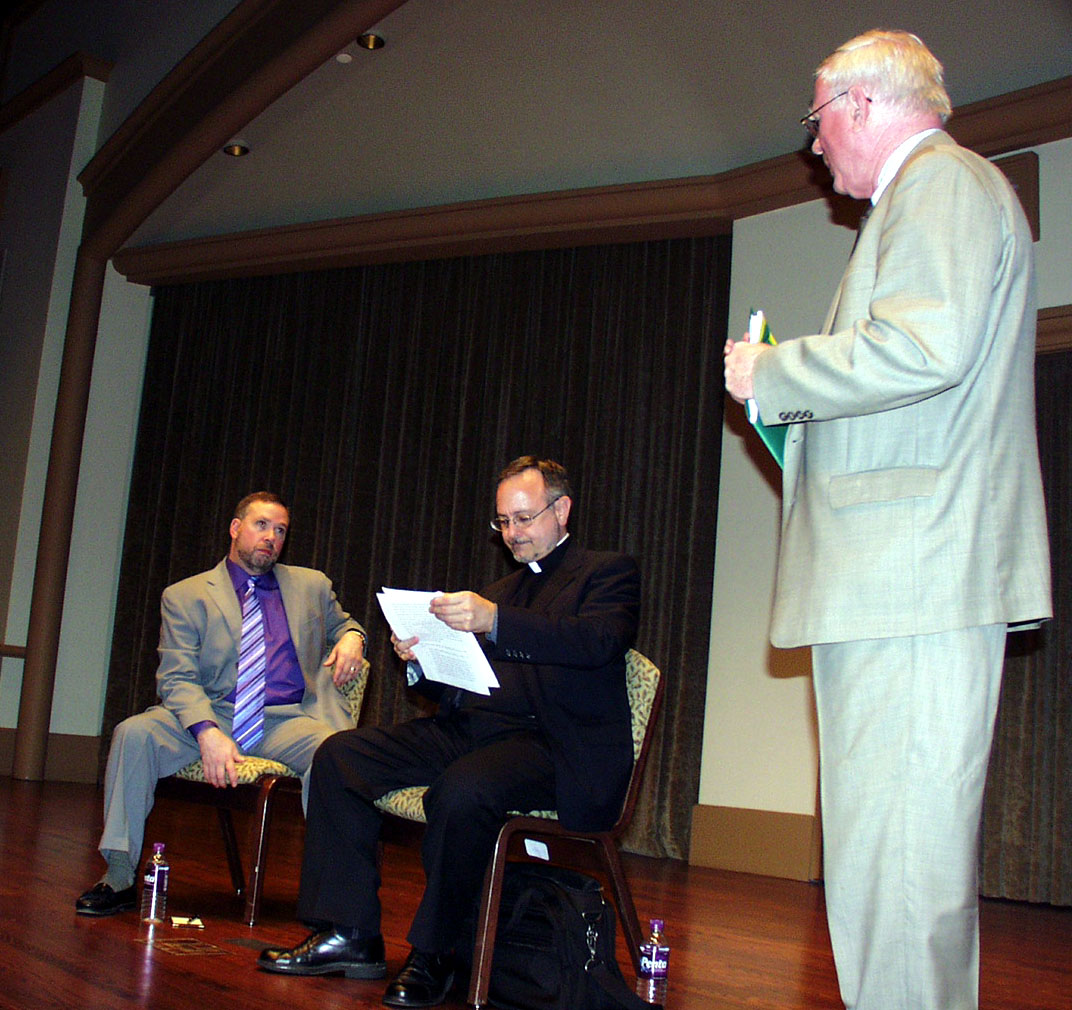

Rabbi

Gary M. Bretton-Granatoor, interfaith affairs director for the Anti-Defamation

League, and Rev. Dr. Francis V. Tiso, associate director for ecumenical and

interreligious affairs for the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops, on Wednesday

evening, May 3, discussed such issues as whether in Catholic belief salvation is

available to Jews, how popular culture lags behind the understanding of

interfaith scholars, and whether the American constitutional doctrine of

separation of church and state retards religious expression. Patrick Drinan,

dean of the USD's School of Arts & Science, served as moderator. Rabbi

Gary M. Bretton-Granatoor, interfaith affairs director for the Anti-Defamation

League, and Rev. Dr. Francis V. Tiso, associate director for ecumenical and

interreligious affairs for the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops, on Wednesday

evening, May 3, discussed such issues as whether in Catholic belief salvation is

available to Jews, how popular culture lags behind the understanding of

interfaith scholars, and whether the American constitutional doctrine of

separation of church and state retards religious expression. Patrick Drinan,

dean of the USD's School of Arts & Science, served as moderator.

The cross controversy

Earlier in the day, U.S. Dist. Court Judge Gordon S. Thompson Jr. ordered the

financially-strapped City of San Diego to remove the large cross from the

mountaintop where it has stood since the 1950s, or pay a fine of $5,000 per day

after a 90-day compliance period. The decision is the latest development

in a controversy that began in 1989 when Philip Paulson filed a suit saying the

presence of the large, landmark cross on the city-owned mountain top violated

his beliefs as an atheist. News of Thompson's decision prompted San Diego

Mayor Jerry Sanders to urge the City Council and the City Attorney's office to

pursue any possible appeals.

Bretton-Granatoor, who is based in New York, and Tiso, based in Washington D.C.,

said they did not want to interject themselves into a local dispute, but were

willing to comment in general on controversies concerning the display of

religious symbols on public land.

Tiso, the first to respond to the question, said “if you do to much of this, it is

a message to society that religious symbolism, and even religious values, has to

go .. inside the house, and that this is an individual matter , a private

matter. Therefore it undermines

the sense of corporate belonging; it undermines the commitment to history; it

undermines the willingness of communities to stand up for ethical values . So

there is a great risk in this.

”I would not be offended by a menorah on top of a mountain,” Tiso added.

“I would not be offended by a

Muslim, or Hindu, or Sikh temple in neighborhood…Those of us who have

traveled, even if they didn’t do religious dialogue as a profession, but just

traveling around the world, become a little more knowledgeable, more tolerant,

more aware – so these things don’t bother me.

In fact I’m proud that someone took a stand and said ‘this is a

symbol of something and God blessed those symbols.’ We risk much by sending

out messages that say, ‘gee, we don’t want to have too much public display

of religion and that kind of thing,” because it is … in my opinion, a

darkness, a strangulation, that is not helpful to anybody.”

Bretton-Granatoor noted the presence in the room of Morris

Casuto, the San Diego regional director of the Anti-Defamation League, and

said on the particular San Diego case he would defer to Casuto. In fact, the local ADL chapter has taken a position opposing

the continued presence of the cross on public land.

In framing his response, Bretton-Granatoor said he was not speaking for

the ADL, but, rather, as a rabbi.

“I have an overarching concern

about the issue of coercion in our environment,” the rabbi said. “I think

the issue of pluralism, and religious freedom, is one of the great contributions

that the United States has made to the world, and to humanity at large. We are a

beacon of light when pluralism is practiced properly.

When pluralism is violated is when coercion is introduced into it, when

somebody uses power that is granted to them either by community, station, age,

authority, to foist their opinion on another – whether it is a teacher in a

classroom, or a military captain with recruits, or in any of those particular

situations where somebody has been forcing a religious belief on another person.

That to me is an anathema to what the United States is all about and should be

fought at every corner.

”On the other hand, I think that we ought to be grown ups, and I think that

there has been a backlash for fear that line has been crossed that forces all of

us to almost neutralize the very religious differences that we celebrate….

Public displays of religious symbols still prick at us, because we know what

happens when you add power to that.

One day soon we should be able to create the kind of American pluralism

that allows us to freely display symbols and not feel that that is a threat to

somebody. But as long as someone feels threatened we need to be sensitive to

that. Because we Jews especially

know what it is like to be coerced, and we know where it leads….”

Public prayer

The rabbi also said he regrets that at public forums religious leaders are

asked to modify their prayers so as not to offend anyone.

He said if a priest wants to pray “in the name of the father, the

son, the holy spirit” it should be understood as the priest simply

expressing his prayer in the manner in which he is accustomed and not as an

attempt to force his religion on someone else.

”I envision a day, soon and in our day hopefully, where Francis, when asked

to pray in front of a mixed assembly, will be allowed to pray as is natural

for him, just as if I were asked to pray I don’t have to create some sort of

namby-pamby vanilla version of something that I hold in my heart to be true,

and that my tradition teaches me.”

Catholic Immigrants

A Jewish woman from Mexico asked why priests in Latin America still teach that

the Jews killed Jesus-- more than 40 years after the Second Vatican Council

issued Nostra Aetate, a document emphatically stating that Jews did not

bear the responsibility for his death. It

is not uncommon, she said, for Mexicans to associate Jews with Judas.

“They depict us as the devil and sometimes they burn him,” she

said.

Bretton-Granatoor responded that the ADL recently surveyed immigrants to the

United States concerning their perceptions of Jews and found that “Latinos

carried the highest percentage of anti-Jewish stereotypes, most of which they

carried here from the church. Why

is that? The answer unfortunately

is really simple and really scary . When

Nostra Aetate was promulgated, it was written in Latin, translated into

Italian, English, French; later on there were German translations and others.

It took seven years, until 1972, before an authorized Spanish translation of Nostra

Aetate was released…

“If I received on my desk notice major change came about seven years ago, I

would take that and throw it out, I wouldn’t pay any attention to it.

And in point of fact, that was what happened. By the time it was

finally disseminated, it really made little impression on the Spanish-speaking

church, and you can go to the young Spanish priests who are still being

trained in what I would consider the pre Vatican II, anti-Judaism . It is

still there.” He added that ADL is now working with the Roman Catholic

Church in Argentina to develop teaching materials rectifying this situation.

Tiso said another dimension of the problem is that biblical texts are “not

just analyzed by linguistic experts. Texts

are copied, decorated, dramatized, processions are derived from them, plays

are written and so on.

”Texts enter into the culture in a rich variety of ways and very often the

fine points are screened out, and mythological elements sometimes are

highlighted. Judas was not a

devil, Judas was a human being with all the risks of that, but for dramatic

purposes you put a couple of horns on his head…. When it becomes a big

cultural thing and all the subtlety is washed out, to make a dramatic point,

then you have to ask yourself a question about consequences.

What are the social consequences of over-simplifying over-dramatizing,

and this is the problem of Mel Gibson’s Passion movie.”

The priest said immigrant communities from other countries must become

acclimated not only to the pluralism of the United States, but to

understanding the role that has been played in America by the Jews.

”The experience of the Jewish community in the United States is a very

particular one, the experience of liberty since the 1650s before the

enlightenment in Europe, and the growth of the Jewish community and its

multitude of institutions, the tremendous contributions – America today is

unimaginable without the Jewish people,” he said.

”I have been telling people of the Arab Christian community that you are in

a tension-relationship with the Jewish community but you have to realize what

they have done to give back to America. Hospitals, universities, chairs of

universities, opera, the constant other contributions of Jewish foundations to

scholarship and so on. So other communities have to think ‘well, what is my

place in this society and in this culture?

I have freedom, I have opportunity; how can I give back culturally?’

It is going to be a long process.”

Jews and salvation

As the two religious leaders engaged in their dialogue, it was clear that

particularly when they were disagreeing with each other, they were careful to

frame their words in a conciliatory manner.

This became apparent as the two discussed Catholic beliefs concerning

salvation.

The rabbi said that there was a

lot of misunderstanding in the Jewish world in 2000 when Cardinal Joseph

Ratzinger—who today is Pope Benedict XVI—issued a statement that seemed to

be saying that the only way to salvation is through the Catholic Church.

Rather than this doctrine being aimed at the Jews, Bretton-Granatoor said,

Ratzinger really was focusing on doctrinal differences within Christianity.

He said that the Vatican at the time had one department for Interfaith

Relations and a separate Commission on Religious Relations with the Jews.

”There are other faiths and then there are Jews,” the rabbi suggested.

“For us (Jews) that is a good thing, not a bad thing. It puts us on a

different plane. It says that the Catholic church has an inextricable link

with the Jewish community and we (the church) have a moral obligation (also)

to make peace with other religious traditions"

Ratzinger’s doctrine “has nothing to do with us...” the rabbi

said.

The priest carefully framed his disagreement with the rabbi’s assessment.

“There

is this idea in Jewish religious

practice of living the Torah in this life, so that the redemptive process is

focused on the corporate body of Israel living its faith in accordance with

the Torah. Christian salvation

emphasizes eschatology—life after death, the state of the soul after death

and ultimately the final resurrection … So once you’ve got that clear you

can understand a couple of things, like why this discussion is often like

apples and oranges – we also talk about living the faith in this life, the

ethical demands of being a Christian, but we do place this great emphasis on

salvation.

“Salvation is one,” Tiso added. “You

can’t have a Buddhist salvation, a Jewish salvation, a Hindu salvation, a

Catholic salvation, etc., etc., as if to say by your spiritual practice you

set up your transcendence in advance. Transcendence—the

state of eternal salvation – is something that God gives us. We believe that

a key aspect of that has been revealed to us by Christ… If you read the New

Testament you can see the diversity of words and images in describing all

that.

”But the salvation of the Jewish people through their faithfulness to their

covenant is the difficult theological point here. Are they saved by that, in the sense that God’s grace comes

to them through that, or are they saved, as are all human beings, by the death

and resurrection of Christ? I

think it would still be well to remember the Catholic doctrine and not

disassociate ourselves from that because we don’t say that the Jews are

saved by their covenant and everyone else was saved by Jesus, because, after

all, Jesus went to the Jews first. So if you cut the two different ways of

salvation completely off from one another, you end up being unfaithful to

Jesus’ primary mission, and…you would kind of undermine the very humanity

of the Jewish people. It is not

salvation through the church, it is salvation through Christ—meaning that

Christ, a Jew, comes into the world to reveal to humanity what it is truly to

be human.

”As we expand our horizons through dialoguing … it is still possible for a

Catholic to say that humanity as consecrated, defined and elevated by Jesus is

universal humanity, including everybody—nobody is outside that mysterious

touch of God into the human condition.”

The dialogue occurred not only in the lecture hall of the Catholic university,

but also in the rotunda of the Kroc Center where members of Hillel, a Jewish

student organization on the USD campus, staffed an information table carrying

literature of interest to both faiths.

|