|

PALOMAR OBSERVATORY—The building housing the 200-inch-diameter

Hale Telescope is one of

the well-known landmarks of San Diego County.

By Donald H. Harrison

PALOMAR MOUNTAIN, Calif.—The people at Palomar Observatory,

where a 60-foot long telescope 200 inches in diameter is the brightest

"star" in a constellation of large telescopes, have far different

perspectives on the weather than their neighbors who live throughout San Diego

County.

For

example, "May Gray" and "June Gloom," the overcast weather

conditions that shroud San Diego County's coastal cities during these two

months, may be sources of complaint elsewhere, but they are welcome developments

for the astronomers. This is because the fog doesn't reach observatory here on Palomar

Mountain, but does block the sources of light pollution below. For

example, "May Gray" and "June Gloom," the overcast weather

conditions that shroud San Diego County's coastal cities during these two

months, may be sources of complaint elsewhere, but they are welcome developments

for the astronomers. This is because the fog doesn't reach observatory here on Palomar

Mountain, but does block the sources of light pollution below.

Twinkle, Twinkle Little Star, What a Big Headache You Are. Poets may

romanticize about the beauty of twinkling stars, but for astronomers the

twinkling effect, caused by air currents in the Earth's atmosphere, make

focusing the big telescope quite difficult.

"June gloom" blanketing coastal San

Diego in background means

less light pollution for Palomar Observatory to contend with.

Many discoveries and legends have been associated with the 200-inch-diameter

telescope as well as with its smaller companions, all operated by the California

Institute of Technology (CalTech) on the 2,000-acre preserve bordering the

Cleveland National Forest. I was delighted to learn that there are a

number of Jewish tales and accomplishments among them.

One of the key players in the saga of Palomar Observatory was Jesse Greenstein,

who built CalTech's prestigious astronomy program, and pioneered research on

white dwarf stars using the 200-inch Hale Telescope. The telescope was

named for astronomer George Ellery Hale, who conceived of the Palomar

Observatory but died before the big telescope was dedicated in 1948.

To explain the white dwarf stars that captured Greenstein's interest, Scott

Kardel, the observatory's public affairs coordinator and a former high school

science teacher, explained that while the sun of our solar system today is in a

state of balance, some day long into the future, "we will have a new

reaction on the inside that will burn hotter, which will make the sun expand and

become what is called a 'red giant.'

"Eventually with the 'red giant,' the outer

layers puff out and the core collapses down to become a white dwarf, about the

size of the earth and weighing as much as the sun—a really dense object that

is very small but very hot. Over time, we think, they cool off and become

what is called a 'black dwarf,' but no one has ever found one. It could be

that no one has ever found one because they are small and dark and hard to find

or it may be that the universe is not old enough to have produced one."

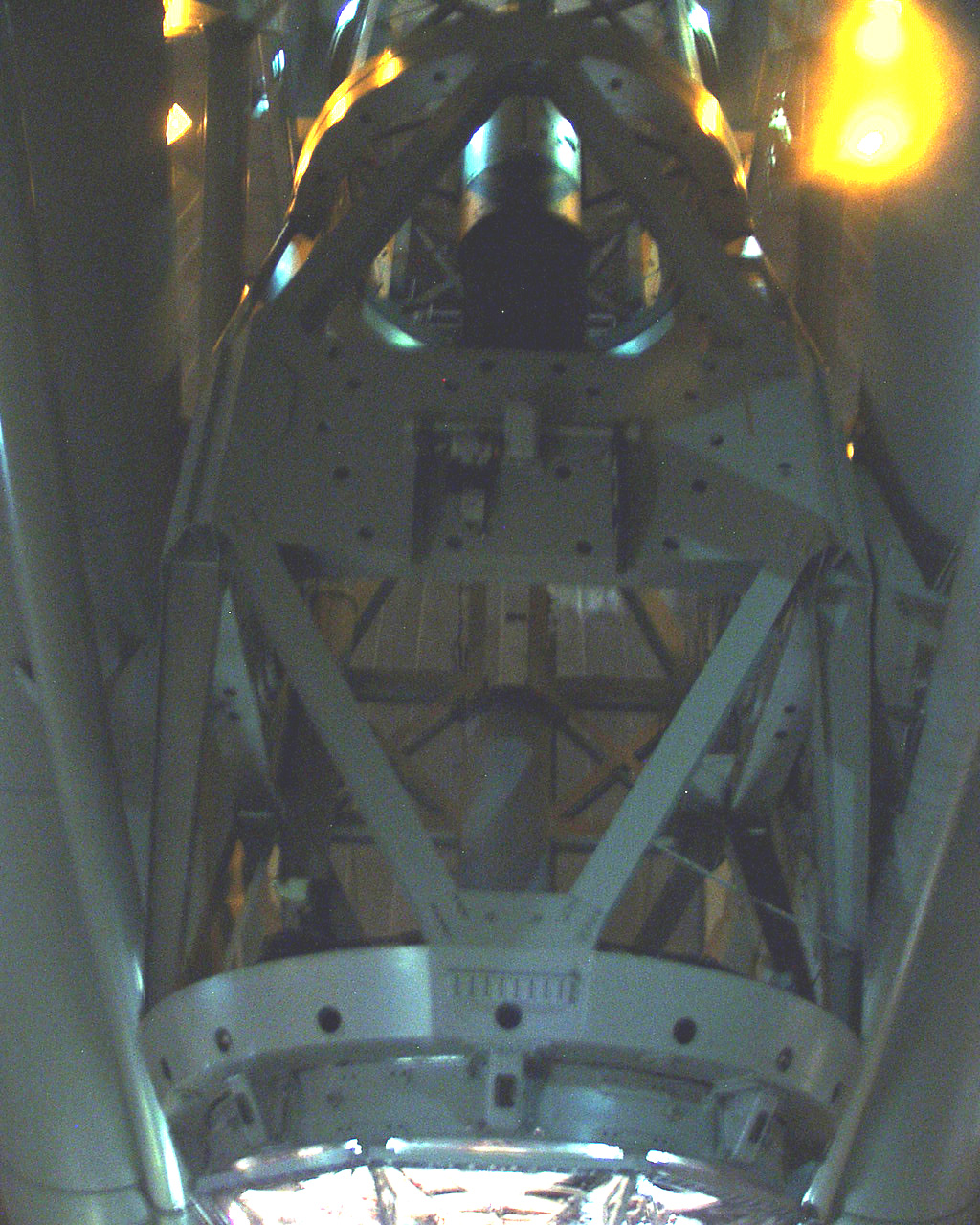

To

observe these white dwarf stars, Greenstein took an elevator from an inside ring

of the observatory to a compartment 80 feet above the floor—an area known as

the "prime focus." From this compartment big enough to accommodate

only one person, an astronomer can select what sector of the sky to

study. Here instruments are calibrated to get the sharpest focus on the

200-inch diameter mirror sitting on a platform below. To

observe these white dwarf stars, Greenstein took an elevator from an inside ring

of the observatory to a compartment 80 feet above the floor—an area known as

the "prime focus." From this compartment big enough to accommodate

only one person, an astronomer can select what sector of the sky to

study. Here instruments are calibrated to get the sharpest focus on the

200-inch diameter mirror sitting on a platform below.

From this station, Greenstein activated a 30-horsepower motor that rotated the

137-foot diameter, 1,000-ton dome of the observatory around the telescope.

A full revolution of the dome could be accomplished in only four minutes.

Another control opened two 125-ton sliding doors revealing the slot that

bisects the dome and exposing the 530-ton telescope to the heavens. For

sake of comparison, Kardel said the telescope is about twice as heavy as the

Statue of Liberty in New York harbor.

Hale Telescope seen from inside the dome

Kardel said the moving parts of the dome, doors, and telescope all were

engineered with such precision, and were so finely balanced, that only small

motors are needed to move them. In fact, he said, astronomers on one

occasion demonstrated how the 530-ton telescope would shift its position under

the weight of a single milk bottle.

As the earth rotates, another small motor is needed to keep the telescope in a

constant position relative to the star or celestial body under study. How

small is this motor? One-twelfth horsepower, said Kardel, prompting my

wife Nancy to exclaim, "that's amazing—our pool motor has more horsepower

than that!"

Kardel said when the telescope is moved from one observation position to

another, it makes an interesting m-m-m-m sound which so fascinated some

Hollywood sound effects people that they recorded it, and used it in one of the Star

Wars movies. "Tragically, it was used when someone was using a

lever to blow up a planet, which is not a very nice thing to do," Kardel

dead-panned.

In a video that Greenstein made before his death in 2002, he joked that one

prerequisite for being an astronomer was to have a cast iron bladder because

there was no place in the cramped compartment of the prime focus area to install

a toilet. Often, events being observed in the heavens were so riveting,

Greenstein or other astronomers did not want to take the time to leave the prime

focus area—not even for calls of another nature..

"Particularly when he was first observing and they were really trying to

push the envelope on things, they would look at very, very faint objects, and

sometimes they would take one photograph that would span the entire night,"

said Kardel.

"If this is the case, this person is at the eye piece, looking at a

reference star with a cross hair, and working to keep the telescope exactly

pointed at that cross hair because it drifts a little. They would correct

it back and they might have to tweak the focus if the temperature changed or

something. That meant the whole night you are glued to this eye piece keeping

the telescope precisely pointed and trying not to think about your

bladder."

With the large dome of the observatory open at night, temperatures could be

quite cold in the prime focus compartment—and Greenstein often would wear

surplus World War II clothing to keep himself warm in his nest in the

observatory atop the 5,600-foot-high Palomar Mountain. Kardel said occasionally

some astronomers would take two thermos bottles up to the prime focus area—one

containing coffee, the other eventually to receive it.

Today, the astronomers don't have to go up to the prime focus

compartment—except to switch out instruments depending on the type of

observation they plan to do. Kardel said one can think of this switching

operation as similar to that of a camera changing lenses—except in this case

the lens, or telescope, remains the same, and researchers switch camera bodies

depending on the type of research being undertaken.

In

this digital age, the images captured by the telescope are relayed to computer

screens in a control room from which they can be studied in comfort. And

there is a bathroom immediately adjacent to the control room. In

this digital age, the images captured by the telescope are relayed to computer

screens in a control room from which they can be studied in comfort. And

there is a bathroom immediately adjacent to the control room.

Besides studying the heavens, Greenstein occupied himself with the recruitment

of faculty and the allocation of telescope time to various researchers—a job

that became increasingly more complex as CalTech brought the Jet Propulsion

Laboratory (JPL) and Cornell University into a consortium governing the 200-inch

Hale Telescope.

CONTROL ROOM—Scott Kardel sits at a control

station at the Palomar Observatory.

Between 60 and 80 research projects a year can be accommodated on the 200-inch

telescope, with observation dates being parceled according not only to the time

of year the phenomenon can best be seen in the skies, but also according to the

weighted value of the research as determined by academic

committees.

Of the 365 nights a year, only 363 are available, because the observatory closes

Christmas Eve and Christmas. Rain and other weather conditions can prevent the

dome from being opened for the night. Soot from the large brush fires of

October 2003 kept the big telescope out of commission for several days, Kardel

said. If ash had landed on the large mirror, in could have formed an acid that

could dissolve the mirror's aluminum coating. Various adverse weather

conditions reduce the number of available observation evenings to about 300 a

year, and these are so closely allocated that if an astronomer is "rained

out," (or "sooted out") there often is no date immediately

available for a make-up session. The astronomer simply has to wait for a

date in the following rotation.

Not all space observations require the 200-inch telescope; some

phenomena can be more comfortably observed using smaller telescopes. There

are seven telescopic arrays atop Mount Palomar, including the Hale; the

Samuel Oschin; an as-yet unnamed 60-inch telescope (philanthropists take

note); a test-bed interferometer (using three small telescopes in concert

110 meters apart); a robotic 24-inch telescope (now being installed); another

robotic telescope called Sleuth (which is used to search for planets around

other stars), and the 18-inch Schmidt telescope (named for optician Bernhard

Schmidt, who designed its lens type.)

200-Inch Model—This concrete circle 200 inches in

diameter is the same size as the mirror used in the Hale Telescope.

Examining it, from left, are Wen-Shion Chang; CalTech's Scott Kardel; Nancy

Harrison, and Ming-Hui Chang.

The late Los Angeles philanthropist Samuel Oschin is another member of the

Jewish community who contributed to the Palomar Observatory saga. Through his

family foundation, he donated his real estate fortune to a variety of causes,

including numerous Jewish communal ones. His gift in 1986 of approximately

$1 million (back when that was considered a lot of money) to CalTech resulted in

an already existing telescope on Palomar Mountain being named the Samuel Oschin

48-inch telescope.

The Samuel Oschin telescope (which like the others is on the mountaintop, not as some

people think when they hear the name, in the "ocean") was the one used

by CalTech astronomer Mike Brown last year to identify the "tenth

planet," nicknamed "Zena" but officially designated 2003 UB313.

The planet is slightly larger than Pluto.

Additionally, the Samuel Oschin Telescope has been used to photograph the entire

night sky of the Northern Hemisphere, while also surveying space for new planets

and asteroids.

CalTech is involved in a different consortium for the use of the Samuel Oschin

telescope. In this one, its partners include Jet Propulsion Laboratory,

Yale University and Indiana University.

The 70-year-old, 18-inch Schmidt Telescope, which predated the Hale Telescope on

the mountain top, had been used for a variety of purposes, but now is being

retired and is likely to serve as a display at the Palomar Observatory. In one

of the last missions for the Schmidt Telescope, David Levy, an amateur

astronomer who writes a column in Sky & Telescope magazine,

teamed up with astro-geologist Eugene Shoemaker and his science-minded wife,

Carolyn, to track asteroids and comets.

The team discovered the Comet Shoemaker/ Levy-9 and tracked it until its

collision in July 1994 with the planet Jupiter. Telescopes around the world,

including the 200-inch Hale Telescope, were trained on Jupiter to watch the

collision.

Currently, Avishay Gal-Yam, a CalTech post-doctoral student from Israel,

is studying such phenomena as gamma rays and stars that go super novae. Palomar

Observatory's automated 60-inch telescope is utilized "to monitor those

exploded stars after the fact—how they fade in brightness in time,"

Kardel said. Additionally, at any time that an orbiting satellite messages

that it has detected a far-off explosion, "our 60-inch telescope almost

instantaneously will observe this."

Sometimes events are of such astronomical importance that Gal-Yam and his team

are required to interrupt other astronomers using the 200-inch Hale in order to

get a better look in real-time at the occurrence, Kardel said.

Nancy and I toured the observatory in the company of our makhetunim from

Taiwan, Wen-Shion and Ming-Hui Chang. We inquired if any foreign universities

are involved in any of the consortia utilizing the various telescopes.

Kardel said that a proposal from Cambridge University in England has been

accepted, which will enable the British institution to soon become a member of

the consortium for the Hale Telescope.

Thus far no formal cooperation with any Israeli organization is on the horizon,

but members of our community can help continue the Jewish saga at the world

famous observatory. Membership in the Friends of the Palomar Observatory

organization costs $45 a year, and offers some behind-the-scenes tours, and

Kardel said he is looking for teachable volunteers who would like to be

docents. More information is available via the website, www.palomar-observatory.org.

|