By Donald H. Harrison

CARLSBAD, Calif—Although Leo Carrillo had become a fairly well known

star on Broadway, it wasn't until after Sam Warner talked him into becoming a

movie actor that his fame became international. With earnings from the movies,

Carrillo was able to purchase in 1937 a large ranch in the hills of Carlsbad

where he brought back to life the romantic traditions pioneered in Spanish and

Mexican California by his own ancestors.

As Carrillo told it in 1961 in The California I Love, which sadly was

still at the printer's when he died, he had been appearing on Broadway when a

company called "Vitaphone" told him they were making four

experimental films with sound tracks to see how the public would react.

He wrote:

"The four attractions which were signed up for the first little short

films were Gigli of the Metropolitan Opera Company, a black-faced comedian

named Al Jolson, the Howard Brothers who sang, and myself. My fee was to

be $2,750 for the day. But there was a slight difficulty. Sam Warner

said to me, 'We haven't got much money so would you take your pay in stock at

25 cents a share?' 'No,' I replied, 'I'd rather have the money because I

am planning to go back to California one of these days and I want to invest

out there.' Al Jolson was more reasonable. He took the stock. It

went up to $400 a share soon afterwards when he did The Jazz Singer, the

first major talkie. I guessed wrong that time!"

The

ten years between the advent of Jolson's singing Kol Nidre in the Jazz

Singer and Carrillo's purchase of the ranch from longtime San Diego County

resident Charles Kelly were filled with movies and friendships with some of

cinema's biggest stars, among them Clark Gable and Carole Lombard, who

vacationed on the ranch. Kelly had named his 1,700-acre spread Rancho de

los Kiotes after the "Spanish dagger" plant that grew on its

grounds, but Carrillo changed the latter part of the name to the more

traditional Spanish spelling of Los Quiotes and purchased an additional 800

acres of adjoining land.

The

ten years between the advent of Jolson's singing Kol Nidre in the Jazz

Singer and Carrillo's purchase of the ranch from longtime San Diego County

resident Charles Kelly were filled with movies and friendships with some of

cinema's biggest stars, among them Clark Gable and Carole Lombard, who

vacationed on the ranch. Kelly had named his 1,700-acre spread Rancho de

los Kiotes after the "Spanish dagger" plant that grew on its

grounds, but Carrillo changed the latter part of the name to the more

traditional Spanish spelling of Los Quiotes and purchased an additional 800

acres of adjoining land.

Other

close friends of Carrillo were humorist Will Rogers, with whom he started in

vaudeville, and writer Irvin S. Cobb. From

Other

close friends of Carrillo were humorist Will Rogers, with whom he started in

vaudeville, and writer Irvin S. Cobb. From

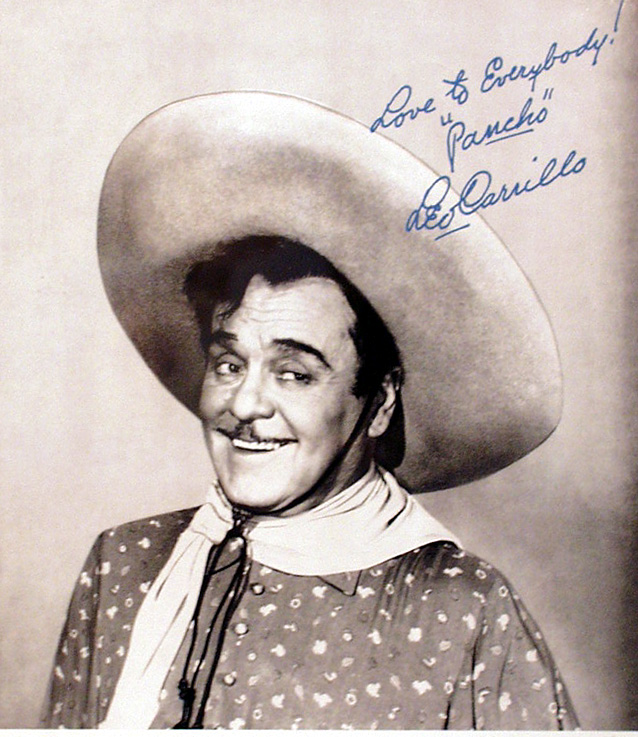

the movies, he transitioned again to television, becoming famous to a

generation of children as the

Spanish Dagger—Los Quiotes

paunchy sidekick Pancho in the syndicated Ziv

Productions television series, "The Cisco Kid," starring Duncan

Renaldo. Carrillo was already in his late 60s and early 70s during the

six seasons he played the humorous Pancho who mangled the English language and

loved nothing more than eating. Cisco Kid was created by the humorist

O'Henry, as an American West counterpart of Don Quixote, coincidentally the

hero of the first book Carrillo ever read. The Cisco Kid shot guns out of

villains' hands, but typically eschewed

violence.

Mementos

of Carrillo's early stage years can be found at a 27-acre

remnant of his ranch that the City of Carlsbad's recreation department

operates as the Leo Carrillo Ranch Historic Park. Inside the main hacienda, Carrillo

is seen at the far right of a photograph along with Harry Houdini, Fred

Stone, Eddie Foy, Louis Mann, E. F. Albee and Will Rogers at the opening of

the E.F. Albee Art Museum and Theatre in Brooklyn.

Mementos

of Carrillo's early stage years can be found at a 27-acre

remnant of his ranch that the City of Carlsbad's recreation department

operates as the Leo Carrillo Ranch Historic Park. Inside the main hacienda, Carrillo

is seen at the far right of a photograph along with Harry Houdini, Fred

Stone, Eddie Foy, Louis Mann, E. F. Albee and Will Rogers at the opening of

the E.F. Albee Art Museum and Theatre in Brooklyn.

Sam Warner, Al Jolson and Harry Houdini all provided Jewish strands for the

tapestry of Carrillo's life, which, off camera, he devoted to the

preservation of California landmarks and to the dissemination of knowledge

about California's colorful past. Carrillo, who served on California's

beach and parks commission, was instrumental to the successful preservation

efforts for the Hearst Castle at San Simeon, the Los Angeles Arboretum, and

Mexican-style Olvera Street, located near his childhood home in Los Angeles.

His family literally was among the first European settlers in California. His

great-great grandfather José Raimundo Carrillo (pronounced "Cay-reel-yo"

by the actor) a leather-jacketed soldier accompanying Father Junipero Serra

and General Gaspar de Portola on the trek in 1769 which established the

mission system in what then was known as Alta California.

Our guide at the ranch, Charles Balteria, filled us in on the

rest of the family's genealogy: Carrillo's great grandfather, Carlos

Antonio, briefly served as a provisional governor of California; the actor's

grandfather was a judge, and his father served as chief of police of Los

Angeles in the late 19th century.

With such a lineage, you might think Carrillo was born to wealth, but in fact

his was a working class family. From downtown Los Angeles they moved to

Santa Monica to farm and fish, and Carrillo worked briefly for the railroads.

He found his way up to San Francisco where he worked as a cartoonist for the Examiner.

His impromptu impersonations and performances prompted colleagues to

urge him to try out for the stage; a career move that led to vaudeville in New

York (telling dialect stories about Mexicans, Japanese, Chinese, and

Italians), and eventually onto the legitimate stage.

After returning to California, Carrillo had his main home in Santa Monica, but

the ranch was his getaway home—the place where he could indulge his love of

California history.

Carrillo emblazoned his flying LC brand not only on 600 head of cattle at the

ranch but also on fireplace mantles, gates, pavings and chimneys. When

the City of Carlsbad took over the property in 2003 (it was donated as a park

by the owners of a nearby housing development), the insignia was added to

various items that can be seen around the ranch, even garbage cans.

Balteria

and recreation leader Tiffan Chilcott led visiting cousin from Louisville,

Harry Jacobson-Beyer, and me, along with others, on a tour that took us from

the small home that was used by the overseer (now the visitor's center) along

a path lined with spineless cactus, which horticulturalist Luther Burbank

developed in the hope of creating an easily replenished source of feed for

cattle. The problem, said Balteria, was that the cattle didn't like the

taste and if they ate too much of it they got diarrhea. But Carrillo

liked the look and safety of them, so had them planted all over. The ranch

house looks like an old U-shaped Mexican hacienda, but that required some

doing. Kelly had added a second story and some pillars to the adobe house

found on his property. After purchasing it, Carrillo had workers take down the

second

Balteria

and recreation leader Tiffan Chilcott led visiting cousin from Louisville,

Harry Jacobson-Beyer, and me, along with others, on a tour that took us from

the small home that was used by the overseer (now the visitor's center) along

a path lined with spineless cactus, which horticulturalist Luther Burbank

developed in the hope of creating an easily replenished source of feed for

cattle. The problem, said Balteria, was that the cattle didn't like the

taste and if they ate too much of it they got diarrhea. But Carrillo

liked the look and safety of them, so had them planted all over. The ranch

house looks like an old U-shaped Mexican hacienda, but that required some

doing. Kelly had added a second story and some pillars to the adobe house

found on his property. After purchasing it, Carrillo had workers take down the

second

Ouchless cactus—Harry Jacobson-Beyer puts

his hand on spineless cactus at Carrillo ranch.

story and the pillars, gut the insides of the first floor, and then

recreate it as the salon, dining room, kitchen complex. To that he had

them add bedroom wings on either side of the old building to give the ranch

the appearance of yesteryear. His wife furnished the house with

antiques, such as might have been brought to California from Boston by clipper

ship. But one bedroom—the horseman's bedroom where Gable and Lombard

stayed—has a western motif where, guide Balteria pointed out, there were

"stirrups on the mirrors, spurs on the door handles, and a rawhide saddle

as a desk chair."

The kitchen had gleaming stainless steel counters suitable for the

entertaining that Carrillo liked to do for his friends from Hollywood.

At one memorable party, Carrillo hosted 200 actors from the Lambs

Players. Edith, a New Yorker who was a bit shy around the Hollywood

crowd, had a small cottage up a hill from the property where she could retreat

into privacy and work as an artist. She also was a collector of Indian

artifacts. Their adopted daughter, Marie Antoinette (Toni), loved the

party life, and as Mrs. Frank Delpy continued the tradition at Rancho de los

Quiotes until she sold the last piece of it in the 1970s.

Besides

the house itself, there is a three-story stable, built on a hill. In

the lower level were stalls for Carrillo's horses, including Conquistador, a

Palomino that he rode in parades and in mounted processions from rancho to

rancho in which people could donate to charity for the opportunity to ride

with him and other celebrities.

Besides

the house itself, there is a three-story stable, built on a hill. In

the lower level were stalls for Carrillo's horses, including Conquistador, a

Palomino that he rode in parades and in mounted processions from rancho to

rancho in which people could donate to charity for the opportunity to ride

with him and other celebrities.

Conquistador, his favorite horse, is buried somewhere on the

property, but the cross that once stood atop the grave has been removed to

prevent anyone from locating and disturbing the remains. The second

floor of the barn is for hay and feed storage, and the third level is a bunk

room for the vaqueros who worked the ranch. Sometimes some of Carrillo's

Hollywood friends would sleep in the bunkhouse, but often, if there were no

room in the main house, they would pitch a tent or drive a trailer onto the

grounds.

A

big beautiful brick barbecue situated near the swimming pool was a perfect

setting for afternoons stretching into evenings with guitar music, and

heaping portions of barbecued carne, under the California sun and later its

stars. One can imagine, at some of the smaller get-togethers, Carrillo telling

his guests stories passed down by his ancestors about early California.

His stories occasionally may have been punctuated by the lulling of cattle or

by the shrill call of peacocks, whose descendants continue to stroll

fearlessly wherever on the ranch they care to go.

A

big beautiful brick barbecue situated near the swimming pool was a perfect

setting for afternoons stretching into evenings with guitar music, and

heaping portions of barbecued carne, under the California sun and later its

stars. One can imagine, at some of the smaller get-togethers, Carrillo telling

his guests stories passed down by his ancestors about early California.

His stories occasionally may have been punctuated by the lulling of cattle or

by the shrill call of peacocks, whose descendants continue to stroll

fearlessly wherever on the ranch they care to go.

To raise funds, the Leo Carrillo Ranch sells his book for $95 a copy,

but if people want a less expensive way to read the actor's warm, nostalgic,

and thoroughly enjoyable stories, copies of The California I Love

always can be found in local

public libraries. Several days before taking the tour, I had checked out a

copy from the downtown San Diego Public Library.

Today the ranch once owned by the actor and preservationist is itself listed as

California Historic Monument 1020. A plaque placed August 6, 1996, is a fine

tribute to this son of California. It reads: "Between 1937 and

1940, these adobe and wood buildings were built by actor Leo

Carrillo as a retreat, working ranch, and tribute to old California culture

and architecture. The Leo Carrillo Ranch, with its flying 'lc' brand,

originally covered 2,538 acres and was frequented by Carrillo and his friends

until 1960. Leo Carrillo was a strong, positive, and well-loved role model who

sought to celebrate California's early Spanish heritage through a life of good

deeds and charitable causes."