By

Donald H. Harrison

Chula Vista, CA (special) -- Rabbi Daniel Menachem Mendel Srugo at 26

is the spiritual leader of the only Sephardic congregation in San Diego

County: the Beth Eliyahu Torah Center located in the Bonita section of

Chula Vista.

If his middle names -- Menachem Mendel -- sound familiar, it is because

he was named after

Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson, the late Lubavitcher rebbe. This

was not because he

was born into a family affiliated with the Lubavitcher movement --

such affiliation didn't

occur until he was nearly a teenager. Rather it was because "my grandmother

could not

have any children for about four years. She asked for a baracha

(blessing)

from all the

tzaddikim (righteous people) and the famous rabbis in Israel

and all over the world, but they

still couldn't have any children. Then they went to the Lubavitcher

rebbe and he gave her a

blessing and right away she became pregnant."

The grandmother bore the daughter who became Srugo's mother, and "my

mother felt she

should have some appreciation. So she called me 'Menachem Mendel.'

Since my father

wanted to call me 'Daniel' they put it all together. But my father

ended up winning: they

call me 'Daniel,' not 'Menachem Mendel.'"

|

But perhaps it was the mother who won after all. After

Srugo's father moved the family from Argentina to Mexico City to establish

a kollel (a center where rabbis study together and teach), its success

in expanding from about four members to 30 was remarked upon by the Chabad

movement. "My father was asked by the head rabbi of Chabad in Argentina

to come back and open a yeshiva for Chabad," Srugo said.

"My father asked a baracha from the rebbe, who told him it was really

a good thing to do, a good and important cause. So he went back to Argentina

and started a yeshiva with five boys who were between the ages of 12 and

14. I was 12. Today the yeshiva has between 50 and 70 people."

A teacher of Torah, Srugo's father, Rabbi Marco Srugo, had been friendly

to Chabad but not a member of it. "But then as you can |

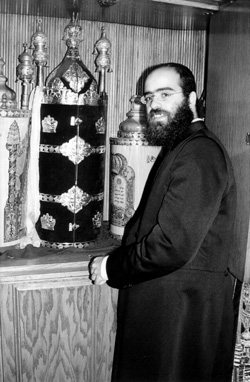

| Rabbi

Daniel Srugo |

influence people, so too can you be influenced, and my father was influenced

for good things by Chabad," Srugo said. "First the children became members

of Chabad, and then my father."

People normally may associate the Lubavitcher chassidim with Ashkenazim

(Jews from Eastern and Central Europe) rather than Sephardim (Jews tracing

their roots to Spain) because the town of Lubavitch, where the movement

had its origins, is in Russia. But Srugo, who was born in Buenos Aires,

Argentina, to Syrian Jewish parents says for a Sephardic boy to become

a Chabad rabbi is not so uncommon. In Israel, he asserted, the majority

of the people affiliated with Chabad are Sephardic, not Ashkenazic in origin.

Through the Chabad movement, Srugo became conversant with the rites

of both the Sephardim and the Ashkenazim. From his father's yeshiva in

Buenos Aires, he went to study for 2 1/2 years in Kiryat Gat, Israel, then

went to another yeshiva in Morristown, N.J.,about a two-hour drive from

Lubavitcher headquarters at 770 Eastern Parkway in the Crown Heights section

of Brooklyn, N.Y.

"It was a very important time in our lives because we (students at the

yeshiva) used to go

every week there to be by the Lubavitcher rebbe for Shabbat," Srugo

said.

From the Morristown, N.J., yeshiva he transferred to another yeshiva

in Montreal,

Canada,

from which he was sent as a shaliach (emissary) to Caracas,

Venezuela, where he served as

a rabbinical assistant. Then he was dispatched to Germany

to serve as a supervisor of kashrut for factories manufacturing

chocolate. He returned to New York after that assignment, then in 1997

he received an important message from a former classmate in Argentina --

Rabbi Mendel Polichenco, who just had become the new Chabad rabbi at the

Centro Social Israelita (Jewish Social Center) in Tijuana,

Mexico.

Polichenco told him he needed some help operating a youth camp in Tijuana,

so Srugo came

to help his old friend. "And I heard that the community of Bonita needed

a rabbi; that their

rabbi (Shlomo El-Harrar) was leaving. One day I was in the neighborhood,

so I came for the

Shacharit (morning prayers) service with them, and they asked me to

come back."

After receiving his smicha (ordination), Srugo began serving the small

congregation as its

rabbi in March of 1998. In a way it was ironic that he came to the

congregation via the

Centro Social Israelita because Beth Eliyahu Torah Center, itself,

could trace its beginnings

to the same congregation.

* * *

Mario Adato was one of the founders of the congregation in Bonita, which

was initially

called Congregation Beth Torah. It was renamed as Beth Eliyahu Torah

Center about four

years ago.

"Most of the members belonged to the synagogue in Tijuana," recalled

Adato, who is in the

leather business, "but the thing was they all wanted to have Sephardic

services and

Orthodox, of course." At the time, the synagogue at the Centro was

led by Cantor Max

Furmansky, who was both Ashkenazic and a member of the Conservative

movement.

Before the new congregation was organized formally, a group assembled

in 1978 for the

High Holy Days in Chula Vista, with Cantor Haim Mizrahi persuaded to

come in from

Mexico City to lead the services.

Afterwards, "we started to think about how we were going to bring him

permanently," Adato

said. "We started working on that and several months after that, probably

the beginning of

1979, we finally brought him to San Diego and started Beth Torah."

|

About 15 families were involved in the start-up of the

new congregation: including those of Mauricio Amos, Morris Benguiat, Abraham

Hanono, Isidoro Lombrosa, Solomon Mizrachi, and Jose Nakash, as well as

Adato himself and his brother, Mauricio Adato. The sisterhood proved to

be an important part of the congregation, and still is, with Licha

Mizrachi, wife of Solomon Mizrachi, serving as the sisterhood's first

president.

Although the congregation's members came to the Mexico-U.S. border area

from a variety of Latin |

| Beth Eliyahu

Torah Center sanctuary |

American countries, their families traced their roots to countries throughout

the Sephardic world, including Israel,

Syria,

and, in Adato's case, Turkey.

Adato noted that Sephardic and Ashkenazic congregations have many of

the same prayers and Torah readings each week, so it is not in content

but in style that the prayer services of the Sephardim and the Ashkenazim

differ. Normally, "we read exactly the same thing but in a different way,"

he said.

On occasion, he said, Sephardim will include in their services "certain

prayers that they don't do and vice versa" but in the main, it is the chanting

that is different. "Remember we Jews went to different countries and we

started singing the way the people of the countries we went to used to

sing. Our cantor conducts the service the Turkish way. And if you have

someone who is from Morocco,

they are going to do it the Moroccan way."

Cantor Mizrahi served the small congregation for about ten years, becoming

known also

throughout San Diego County as a mohel, before moving to a position

in the Los Angeles area. The congregation was then and still is now too

small to afford both a full-time rabbi and a full-time cantor. It chose

to seek a rabbi, rather than a cantor, as Mizrahi's replacement. The first

man they hired came from Argentina, but Rabbi Ben Shimon returned there

in less than a year, for a better financial opportunity. Next came Rabbi

Shlomo El-Harrar, an Israeli of Moroccan parentage, who served the congregation

for five years before moving on to Miami about two years go.

During El Harrar's tenure, founder Solomon Mizrachi offered the congregation

a deal it could not refuse. It could have for its home a group of buildings

Mizrachi owned at the intersection of Bonita and Central Avenues, provided

that the congregation agree to remain both Sephardic and Orthodox and that

it rename itself as Beth Eliyahu Torah Center in memory of Mizrachi's father,

Elias Mizrachi. Also the congregation would have to make a payment of $1

a year.

|

"But in truth he didn't really want the $1 a year," laughed

Adato, a former president of the congregation. "His family pays far beyond

that in their dues, and some of them don't even live here. They live in

Panama."

Solomon Mizrachi later died, but his family remains quite active in

the congregation' affairs. His brother Mo and sister-in-law Grace Mizrachi

recently moved to the community from Panama

City to be closer to their sons, Michael and Rafael. The

latter is the congregation's current president. |

| Exterior of Beth

Eliyahu Torah Center |

Adato recalls that "Rafael and I went to see Rabbi (Yonah) Fradkin (of

Chabad of San

Diego) and asked him if he could send us a young rabbi, a student rabbi,

from the yeshiva of

Chabad but we wanted a Sephardic rabbi." As it turned out, Srugo already

was preparing to

come to help Polichenco in Tijuana.

"Rabbi Srugo is very young, but he has a lot of good things going for

him," Adato said. "We

wanted a very young rabbi so he would be attractive to children and

to very young people.

Because we really think the future of our congregation is young people.

If they get used to

coming to the synagogue and getting involved with Judaism, with a young

rabbi there are

more chances that they an continue coming."

Adato estimated the congregation now has between 70 and 90 families,

"but thank God

certain families have two or three (adult) children and when they come

it is not hard to have

a minyan.

"When we get a little more strength what we would like to do is start

inviting guest speakers

to give some classes or lectures to the congregation about Sephardic

culture and Judaism in

general, but it will take a little more strength."

* * *

HERITAGE readers may be familiar with Grace Mizrachi from the series

that

we did on the

Jewish community of Panama last March. Now ensconced in a home in Bonita,

the

outspoken mother of Beth Eliyahu Torah Center's president is on a campaign

to forge

greater bonds of unity not only among Sephardic Jews but among Jews

generally.

In some places in the Jewish world, Mizrachi says, the assimilation

rates seem as high as 80

percent, which she compares to a "second Holocaust" insofar as its

possible effect on the

Jewish population. Inspired by the work of Dr. Jose Nissim in Los Angeles,

who has built a

Sephardic Center there as well as another Sephardic Center in Jerusalem,

the energetic

Mizrachi advocates creating a Sephardic Center in Bonita that would

serve

Spanish-speaking Jews from both sides of the U.S.-Mexico

border in particular and all Jews,

including English-speaking ones, in general.

Although they are not related by blood, she and Nissim have a common

aunt. Having been

a financial supporter of Nissim's centers for over 20 years, she enthused

that "his name

'Nissim' means miracles and miracles took place." However, she said,

"I told him that I

have problems with the name 'Sephardic Center' because my daughters-in

law are

Ashkenazic. So we should say that it is the 'Sephardic Center in Jerusalem

for all Jews.'

He said 'okay, write me a letter, and I did, and any time I get a letterhead

without the 'for all

Jews,' I remind him and right away he will rectify it."

Nissim, she said, is a miracle worker. "They have 200 people coming

every Monday night

over there in Los Angeles" to attend lectures and other cultural events.

Recently, the Los

Angeles center staged a Shabbaton for young adults at the Rosarito

Beach Hotel in Baja

California. It was attended by a couple of youth from Beth Eliyahu

Torah Center, and won

high marks from Rabbis Srugo and Polichenco, according to Mizrachi,

because kashrut and

Shabbat were strictly observed.

* * *

Over a lunch at Sheila's Restaurant in the Clairemont area of San Diego

-- one of only a few

establishments in the San Diego-Tijuana region where one can have a

kosher meat meal -- I

asked Rabbi Srugo his feelings about a Chabad-led congregation working

closely with the

Sephardic Centers (for all Jews) in Los Angeles and Jerusalem

"In the Torah it says that if you have a rope that is made from three

ropes, it will be much

harder to break," he replied. "If you have the Yellow Pages (of the

telephone directory) and

you try rip each of these pages, they are thin. But try to rip the

whole thing together it would

be impossible. As long as we get together, it makes us only stronger.

As long as it is done

the right way, we can work together and bring the communities together."

Like Mizrachi, Srugo does not want the distinctions between Ashkenazim

and Sephardim to

be overstressed. Like her, the rabbi has a good family reason. About

a year ago, he married

the former Esther Applebaum, an Ashkenazic, Orthodox woman of Argentine

background

who grew up in Brooklyn. As this edition of HERITAGE was going to press,

the couple

was expecting a first child.

They were married after Srugo took his post at Beth Eliyahu, and already

she had made an

important difference to the congregation, the rabbi said. "All the

help and support she

gives," he said with enthusiasm. "Sometimes a man cannot communicate

the same thing to

a woman as a woman can. As much as I tried to communicate with girls,

she was able to do

it the right way!"

Instead of making the differences between Ashkenazim and Sephardim a

reason for division,

Srugo said, they should be a reason instead for celebration. Each group

can learn from the

other, he said.

"Some things among the Ashkenazim are more strict and some things for

the Sephardim are

more strict," he said. "For example, on Pesach it seems the Ashkenazim

almost don't eat

anything. Many vegetables they don't eat likes beans and rice, but

the Sephardim will.

Some Ashkenazim in Chabad will not eat matzoh if it gets wet, so they

won't allow matzoh

in anything, not in chocolate, for example. Whereas we will eat matzoh

with everything."

Among some Sephardim, he said, there is a custom of not eating anything

before morning

prayers -- a stricter standard than the one followed by Ashkenazim

in Chabad. "What the

rebbe said is that it is better for a person to eat in order to pray

than to pray in order to eat,"

Srugo said. If someone is irritable, "he is not going to be able to

concentrate, so it is better to

eat something before the prayers."

While on the subject of food, Srugo mentioned that there is a Sephardic

custom associated

with beans known in Hebrew as rubya. Because the name of the Hebrew

prayer She Yirbu,

beseeching God to increase our merit, has a similar resh-bet letter

combination in its name, a

custom is to eat rubya "so that we should have a lot of merit in front

of HaShem."

After telling stories about how customs vary between Sephardim and Ashkenazim,

Srugo

emphasizes this point: "We are all the same. We all came out of Egypt.

We all received the

Torah together. It doesn't make any difference what the customs are.

At the time of the

Talmud, we saw people arguing days and days about a certain law. They

were trying to find

the truth, and so they were still friends. Today, the reason that we

have different customs is

that we should become better, not that we should fight.

"I will give you an example. In our congregation, we have people from

all over -- Turkey,

South America, Israel, Americans. Instead of one saying about the other

'No, I don't like

him because he doesn't have the same customs I have,' we say 'okay,

because we are people

from so many different place, let's teach each other about the nice

customs that we have and

let's try to learn from each other.'"

Such multiculturalism among Sephardim also should be and is extended

to Ashkenazim,

said the rabbi. "It used to be, many years ago, that if you got married

to an Ashkenazi, you

were considered not good anymore; you would have to look for another

place. Today,

thank God, it isn't like that any more. We know, people have come to

realize, that we are

all Jews and we are all part of one big unity."

|