|

By Donald H. Harrison

SAN DIEGO—Earlier this month, I reviewed A Tale of Zabokretch about the pogroms in Ukraine during the early 20th century. Written by Ben Finn, it was a puzzle. It was a story of drunken, hate-filled anti-Semitic mass murder – the kind of violence that earns movies “R” ratings or at least “PGs”—and yet it was written in a simple declarative style, as if intended for young children. Who was Finn’s intended audience? I had wondered. SAN DIEGO—Earlier this month, I reviewed A Tale of Zabokretch about the pogroms in Ukraine during the early 20th century. Written by Ben Finn, it was a puzzle. It was a story of drunken, hate-filled anti-Semitic mass murder – the kind of violence that earns movies “R” ratings or at least “PGs”—and yet it was written in a simple declarative style, as if intended for young children. Who was Finn’s intended audience? I had wondered.

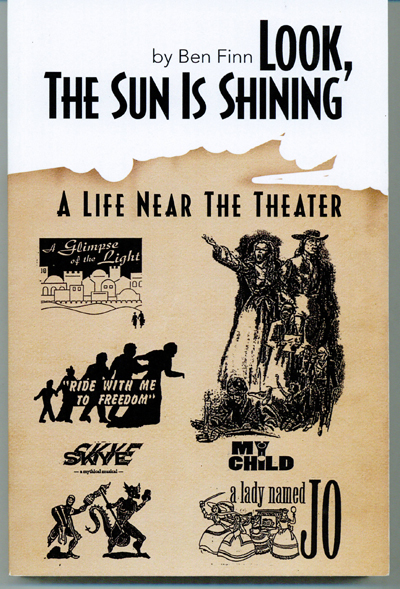

Finn responded that age group of his audience may indeed be problematic, but noted that his own grandchildren had found the book interesting. He also sent me another book, his memoir, Look The Sun Is Shining: A Life Near The Theater. The title and subtitle are most instructive. “Look The Sun is Shining” conveys hope, like the beginning of “Tomorrow,” the signature song of the musical Annie: “The sun will come out tomorrow…” Finn published this memoir when he was 81 years old, and it’s the subtitle that tears at the heart: “A Life Near The Theater.” Not “in” the theater, "near" it. Oh, how Finn would have loved to change prepositions.

“Look, the Sun is Shining” was also the title of the first song Finn ever wrote, coming hopefully enough during World War II. Over a lifetime, he composed more than 700 songs. Most of them were for musicals that he either authored directly, or collaborated upon, many carrying with them the hope—later dashed—that they somehow would get to Broadway, somehow propel Finn from near the theater to inside.

While reading the book, I kept thinking of the Willie Nelson song, “Mammas Don't Let Your Babies Grow Up to Be Cowboys.” However, in my mind’s ear, I heard Willie singing “Mammas Don’t Let Your Babies Go Into The Theater” because Finn’s cautionary tale is one of broken promises, rivalries, unethical behavior, backstabbing, and other business experiences that one can suffer while trying to bootstrap oneself into theater fame and fortune.

Song after song, musical after musical, seemed to be paving Finn’s way to the big time, but were only to encounter road blocks. Readers of this memoir seemingly realize before Finn does that his hoped for success may never be—that storm systems seem to stalk his shining sun.

We can be appreciative that Finn had his regular work — teaching and dramatic coaching in the New York public school system—exposing generations of children to the joy of performance, if not of composing. His wife, Bernice, clearly

Go to the top of right columns

|

|

is the blessing of his life. She not only tolerated but also encouraged Finn as he invested good portions of his teacher’s salary into having the music of his songs transcribed, and paying singers to audition his material. She co-suffered the many producers, directors, and investors who, in one fashion or another, led Finn down twisting roads of disappointment.

Is this a bitter book? Perhaps, even a depressing one, at times. However, it is also inspirational. Finn composed musicals about a variety of subjects, with his Jewish social conscience often leading him to choose as topics great, important issues, such as the struggle to create Israel, and the triumph over slavery of such inspirational African Americans as Harriet Tubman and Phyllis Wheatley. One cannot help but hope that Finn’s remarkable perseverance will somehow, someday prove anew Theodor Herzl’s wonderful axiom: “If you will it, it’s not a dream.”

|

|