|

By David Amos

SAN DIEGO—The Jewish people have been in the mainstream of music making throughout the ages. We have all heard of comments and jokes about how many of the famous violinists of the world are Jewish, or about the vast number of Jewish musicians who have immigrated to Israel. SAN DIEGO—The Jewish people have been in the mainstream of music making throughout the ages. We have all heard of comments and jokes about how many of the famous violinists of the world are Jewish, or about the vast number of Jewish musicians who have immigrated to Israel.

This is all good and well, but how about composers? Up to about the beginning of the Twentieth Century, surely there were well known Jewish composers here and there, but the Jews earned themselves a reputation of being talented “re-creators” of music, more than the initial inspiration. Many times, discrimination, lack of opportunities, and open anti-Semitism contributed to this.

This all changed in the early 1900’s. In my conducting trips to various Eastern European and Russian orchestras, many times I had conversations with local reporters and musicians, and not surprisingly, the subject was “American Music." The composers we discussed who were invariably mentioned as true examples of 20th Century American Music, were Aaron Copland, Leonard Bernstein, and, of course, George Gershwin. All three were Jewish.

I can assure you that there are literally hundreds of other Jewish-American composers whose music is worthy of our attention, but, clearly, the ones most frequently quoted are the dynamic trio mentioned above.

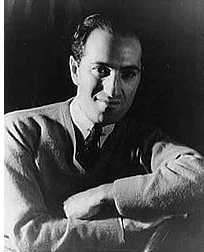

In 1998, we celebrated the centennial year of the birth of George Gershwin (1998-1937), the earliest of the three. More than any other composer, he established a clear “American” music idiom through the fusion of popular tunes and Jazz into the concert hall. His personal influences were the classical symphonic music his parents cherished, the synagogue chants of his early years, the music of Tin Pan Alley, and the music clubs of Harlem.

He changed American music forever. But the point isn’t that Gershwin was purposely crossing boundaries, but he did not recognize that there were any boundaries to cross.

Although we are all very familiar with most of Gershwin’s symphonic output, here are a few facts which you may find interesting: With all the attention which orchestras give to his works, it is surprising to know that if we played all six of them, back-to back, it would only take one hour and forty minutes! Their titles? Rhapsody in Blue, Piano Concerto in F, An American in Paris, Second Rhapsody, Cuban Overture, and Variations on “I Got Rhythm”.

Even after Gershwin had already achieved fame and fortune,he was always uncomfortable that he never had formal music training. Yes, a few lessons here and there, but never the disciplined, grueling studies of history, harmony, form,

orchestration, and counterpoint. To this end, he was notorious

Go to the top of right column

|

|

for approaching great and famous composers whom he met in social events, and asking them for lessons. All of them turned him down, a few with a clever or polite remark, or others with less diplomacy. for approaching great and famous composers whom he met in social events, and asking them for lessons. All of them turned him down, a few with a clever or polite remark, or others with less diplomacy.

Why? These two stories may shed some light into the subject. When Gershwin (at right, circa 1937) asked Maurice Ravel for lessons, the latter replied, “Why would you want to be a second-class Ravel, when you are already a first-class Gershwin?” The quick-witted Igor Stravinsky responded to the same request by asking Gershwin how much money he had earned during the past year. When he heard Gershwin’s answer, which was a fairly big amount for its time, Stravinsky replied, “Then, you should be giving me lessons!”

The super-serious and still the most misunderstood composer of the 20th Century, Arnold Schoenberg, used to play tennis with Gershwin when they both lived in the Los Angeles area. He defended Gershwin, and said that he was “a man who lives in music, and expresses everything, serious or not, sound or superficial, by means of music, because it is his native language”.

Most musicians had realized something that Gershwin himself may not have grasped: That his music was so fresh and original as it was, that formal lessons could only harm his wondrous creative process. His genius was a gift that no teacher or conservatory could improve.

What makes Gershwin’s songs so special is that unlike the songs of many other famous and talented songwriters of his generation (such as Irving Berlin, Jerome Kern, Cole Porter, Richard Rodgers), the melody was not his most important element, but the harmonies and the bottom, the bass line. The other composers, more often than not, wrote the melody and many times left it to others to harmonize and orchestrate. Not Gershwin. What does this mean? The strong harmonic structures allow Jazz musicians and arrangers to improvise on the songs, and this has opened Gershwin’s music to be interpreted by so many other artists of our time. Each one of his creations went on to have a life of its own beyond the simple rendering of the original song.

Many composers have combined classical and popular music forms, but none has done it with the skill and creativity of Gershwin.

Even though Gershwin’s life was tragically short, and even though there are still many musical snobs who still argue that his works do not belong in the concert stage next to the other more “legitimate” composers, his symphonic compositions, Porgy and Bess and his innumerable songs and Broadway shows are still, and likely to continue being favorites of audiences everywhere. He undoubtedly is an essential part of music history.

|

|