|

By Donald H. Harrison

LA MESA, Calif.—Holocaust survivor Eve Gerstle had as her

houseguest last week the chairperson of the Active Museum of Jewish History,

which is based in her hometown of Wiesbaden,

Germany—the city from which she and her parents, Arthur and Sophie Wertheimer,

were deported by the Nazis in 1942 to the Czech ghetto of Terezin. Gerstle's

parents died of illness caused by unhealthful living conditions and

starvation in the ghetto.

Gerstle, 91, who is believed to be the last living survivor of the large group

of Jews who were deported from Wiesbaden on August 30, 1942, has been

acquainted for nearly two decades with museum chairperson Dorothee

Lottmann-Kaeseler, 62. The museum official, born in Krakow, is the daughter of a German

railroad engineer who was stationed in occupied Poland, and who disappeared at

the end of the war. The question of what her father did—and what his exact

role might have been in transporting Jews to their deaths—has haunted

Lottmann-Kaeseler most of her life. "He must have known," she says

grimly. Like many Germans of that age, her mother refused to discuss the

war with her.

Lottmann-Kaeseler came to the San Diego suburb of La

Mesa to carry out two missions. First, she presented a packet of

materials to Gerstle concerning the recent installation of a pair of

"stumbling stones" on the sidewalk in front of the house at Biebricher

Allee #33 where the Wertheimers had lived until their deportation. The stones

are not meant to be physically stumbled over, but rather are installed for

passersby to "mentally stumble upon," and be "made aware of the

many places where the people resided," Lottmann-Kaeseler said.

Artist Gunter Demnig conceived of the project memorializing German Holocaust

victims, and, more than 7,000 such stolpersteine thus far have been

placed throughout Germany. The names of the Wertheimers were chosen by

Bertram Theilacker, a banker with Nassauische Sparkasse who wanted to honor someone in his

profession. Arthur Wertheimer also had been a banker.

In a personal note that Lottmann-Kaeseler carried to Gerstle, Theilacker

explained that he wanted his two elementary school-aged children to understand

that in the Holocaust that no matter what a person's profession, he or she was

not immune from the Nazi tyranny. He said the Nazi crimes against Jews

were so "unfathomable, the children kept asking 'why, I cannot

understand.'" He said he felt it important to teach his children that

"democracy and tolerance don't fall from the sky, you have to work for

them."

The two children—Moritz, 10, and Nele, 7— also wrote notes to Gerstle,

telling her about their interests in sports and other activities and wishing her

health and long life.

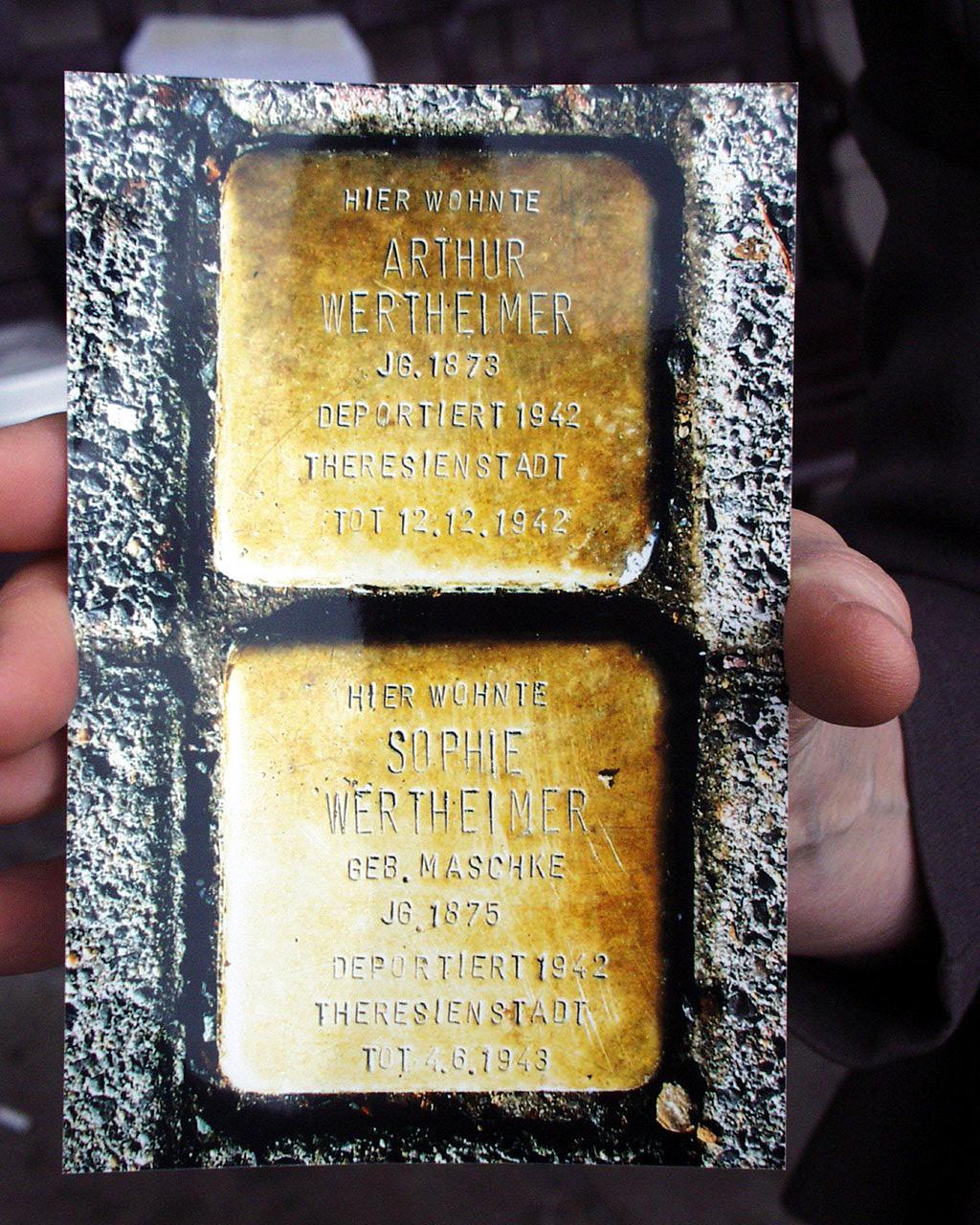

Photos brought to Eve Gerstle from Wiesbaden by Dorothee

Lottmann-Kaeseler show the stumbling stones created

in her parents' honor, telling their names, birth dates, the fact that they had

lived in the building shown in the second

photograph, that they had been deported to Theresienstadt (German name for

Terezin) and giving the dates of their

deaths. Arrow in second photo shows where the stumbling stones were

installed, and third photo shows artist Gunter

Demnig installing the stone. The man in topcoat behind him is Bertram.

Theilacker, the banker who not only paid for

the stones, but was able to convince his bank to donate funding for Lottmann-Kaeseler's research trip to the

U.S.A.

Gerstle previously

had been honored by the City of Wiesbaden with a gold medal

in recognition of the lecturing she has done about her

experiences in the Holocaust both in Germany and in the United States.

With Gerstle's 92nd birthday approaching April 20, Lottmann-Kaeseler's

second purpose for visiting her was to videotape her recollections of her life

in Wiesbaden before the deportation, and to learn what had happened to her

since.

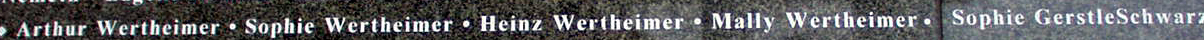

I was privileged on Friday, March 31, to drive the two women to the Holocaust

Memorial Garden at the Lawrence Family Jewish Community Center where the names

of members of Gerstle's family are listed along with many other victims of the

Holocaust.

After

visiting the monument, Gerstle next took Lottmann-Kaeseler upstairs to the Astor

Judaica Library to see the Holocaust book collection, which was dedicated in

honor of Gerstle by Hal

and Eileen

Wingard. Gerstle will play an important role in the upcoming San Diego

Music Festival, which Eileen Wingard has helped to organize. Gerstle and San

Diego residents Margot Cohn, Lilli Greenberg and Ruth Sax will tell of their

personal experiences in Terezin in a panel presentation at 7:30 p.m., Tuesday,

May 16, at the Lawrence Family JCC in La Jolla. After

visiting the monument, Gerstle next took Lottmann-Kaeseler upstairs to the Astor

Judaica Library to see the Holocaust book collection, which was dedicated in

honor of Gerstle by Hal

and Eileen

Wingard. Gerstle will play an important role in the upcoming San Diego

Music Festival, which Eileen Wingard has helped to organize. Gerstle and San

Diego residents Margot Cohn, Lilli Greenberg and Ruth Sax will tell of their

personal experiences in Terezin in a panel presentation at 7:30 p.m., Tuesday,

May 16, at the Lawrence Family JCC in La Jolla.

The panel discussion was organized in connection with a recital to be performed

on the preceding evening by violinist Zina

Schiff entitled "Music Played in Terezin." The performance

will include pieces performed by inmate violinist Karel Frölich in the concentration

camp, which the Nazis maintained as a "show ghetto" to deceive the

International Red Cross about their genocide against the Jews in other camps.

We drove from the Lawrence Family JCC to Congregation

Beth Am in the Carmel Valley section of San Diego so Gerstle and

Lottmann-Kaeseler could see the re-creation of a wall from the Jewish burial

house of Roudnice, Czech Republic, the town from which that Conservative

congregation's Holocaust

Torah originated.

A ritual at Congregation Beth Am since its early days in rented quarters in

suburban Solana Beach was for children at their b'nai mitzvah ceremonies to read

from that Torah, thereby linking themselves to children of Roudnice who

perished. When the congregation built its new home in Carmel Valley, it

replicated the wall to make the linkage even more tangible.

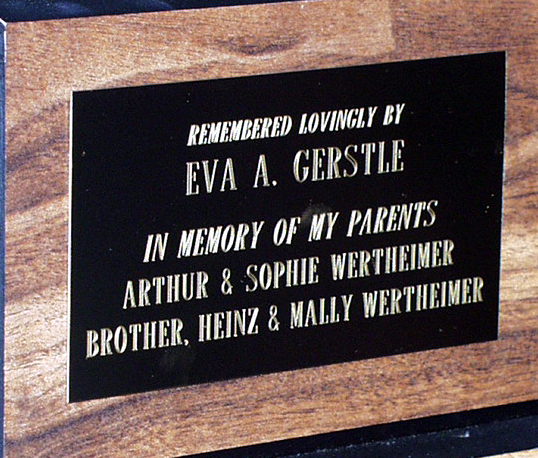

Next

we traveled to the San Carlos section of San Diego to Tifereth

Israel Synagogue, the Conservative congregation where Gerstle is a member.

As Lottmann-Kaeseler's videotape rolled, the synagogue's executive director,

Regina Wurst, showed us through the sanctuary where another Holocaust Torah is

the centerpiece of a display in which plaques memorialize the murdered families

of Gerstle and other members of the New Life Club. That club of Holocaust

Survivors meets monthly. Originally having more than 120 members, the club

has been "shrinking," because many members are elderly, Gerstle noted. Next

we traveled to the San Carlos section of San Diego to Tifereth

Israel Synagogue, the Conservative congregation where Gerstle is a member.

As Lottmann-Kaeseler's videotape rolled, the synagogue's executive director,

Regina Wurst, showed us through the sanctuary where another Holocaust Torah is

the centerpiece of a display in which plaques memorialize the murdered families

of Gerstle and other members of the New Life Club. That club of Holocaust

Survivors meets monthly. Originally having more than 120 members, the club

has been "shrinking," because many members are elderly, Gerstle noted.

The

mantle of the Holocaust Torah, created by textile artist Jacqueline

Jacobs, was

inspired by "The Butterfly," a well-known poem from Terezin written

by Pavel Friedman which said among the sights one never gets to see in the

ghetto is a butterfly. Jacobs' mantle shows a barbed wire on which a butterfly

is trapped, a symbol of the Holocaust. Above, butterflies flying in the bright

sunlight represent liberation and freedom. The Hebrew inscription on the

Torah mantle is Ani Ma'anim, "I believe," which is considered

an anthem by some Survivors, expressing the belief that even though God may

tarry, He still is with us. The

mantle of the Holocaust Torah, created by textile artist Jacqueline

Jacobs, was

inspired by "The Butterfly," a well-known poem from Terezin written

by Pavel Friedman which said among the sights one never gets to see in the

ghetto is a butterfly. Jacobs' mantle shows a barbed wire on which a butterfly

is trapped, a symbol of the Holocaust. Above, butterflies flying in the bright

sunlight represent liberation and freedom. The Hebrew inscription on the

Torah mantle is Ani Ma'anim, "I believe," which is considered

an anthem by some Survivors, expressing the belief that even though God may

tarry, He still is with us.

Our discussion about Lottmann-Kaeseler's mother never wanting to talk about the

Holocaust prompted Gerstle to disclose while we drove from one synagogue to the

other that she, too, had not wanted to talk with her children about her life at

Terezin and later at the Auschwitz and Stutthof camps.

She disclosed that she used to wear a bandage over the Auschwitz tattoo on her

arm because people in grocery stores, not knowing what the numbers represented,

would inquire if that were her telephone number. One night, she said, her

teenage daughter, Susi, burst into the bedroom of herself and her late

husband, Julius Gerstle, and was in tears after returning from a date with a

boy. The daughter was so distraught she could not tell her parents what was the

matter, but promised to talk with them the next morning. Gerstle recalled that

she could not sleep that night, so worried was she that something terrible might

have happened to her daughter on her date.

It turned out that Susi and her escort had gone to see the movie, The

Pawnbroker, which in 1964 was one of the first to portray what had happened

in the camps. Susi wanted to know if this was what had happened to Gerstle and

to her first husband, Ari Zwick. At that point, Gerstle realized it was time to

tell the story of her experiences in the camps, and of her return in 1946 to

Wiesbaden to search in vain for members of her family. It was in

Wiesbaden, which then was in the American Occupation Zone, that she met Julius

Gerstle, an American soldier encamped nearby. The story of Gerstle's experiences

was so difficult for Susi to listen to, that she protectively urged her mother,

"don't tell Jackie," her sister, who is three years younger.

After

that emotional experience, talking about the Holocaust gradually became easier

for Gerstle, who thereafter spoke to schoolchildren in the United States—helping

to spread understanding of the Holocaust A movement in Wiesbaden to

grapple with its past led to an invitation to Gerstle from the officials of that

city to return for a visit. She returned several times to her home town as

a lecturer.

Lottmann-Kaeseler lived in Kent, Ohio, for a year as a high school exchange

student, and speaks English with very little accent. She said she also had

as a gymnastics teacher in Essen, Germany, a remarkable Jewish woman who had hidden

through the Holocaust and who spoke freely to her students about her experiences

and about her family in Israel. "She taught us Hebrew songs,"

Lottmann-Kaeseler recalled.

Trained as a legal researcher, Lottmann-Kaeseler became fascinated by the Jewish

world in its many aspects, not just the Holocaust. She has traveled to

Israel, spent time on a kibbutz, participated in Wiesbaden-Kfar Saba sister city

events and, as the museum's chairperson, has overseen exhibitions on various

facets of the Jewish experience, including the lives and works of well-known

Jewish authors.

I mentioned to Lottmann-Kaeseler that mystery writer Faye

Kellerman recently had spoken at the Lawrence Family JCC and had commented

that seeing the many monuments in Germany to the Holocaust had prompted

mixed emotions. She was pleased that the Germans will not forget, but at

the same time wondered if its right to constantly make Germans feel guilty.

Lottmann-Kaeseler commented that German history "will be burdened with this

forever," and that the world's memory of the Holocaust is not

something that ever will go away. It is important for German society to ask

itself "how is it possible that people can do this?" and "what

was the makeup of German society that made it possible?" These will

always be important questions, she said. In facing up to their past,

Germans draw lessons that will impact their future.

|