|

By David Amos

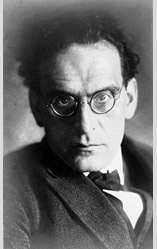

SAN DIEGO—Some time ago, I made an impulse purchase of a couple of compact discs containing music by Beethoven, conducted by the legendary Otto Klemperer (pictured in Wikipedia photo at right) SAN DIEGO—Some time ago, I made an impulse purchase of a couple of compact discs containing music by Beethoven, conducted by the legendary Otto Klemperer (pictured in Wikipedia photo at right)

There is nothing unusual about that. I already own the complete nine symphonies on long play records which were released in the 1960’s on the Angel label. I am sure that many of you may have the same collection on LP or CD, and are familiar with this great conductor’s celebrated interpretations of Beethoven and other German composers.

But these two CDs served as a re-acquaintance, finding an old friend I have not seen in a long time. Just as if one were hearing Chopin’s piano music played by Artur Rubinstein, everything sounded “just right." There he is, the master, giving us renditions of such weight and depth, that we can not help but admire, respect, and enjoy what we hear.

Never mind that many of his tempos are much slower than we are used to hearing. Never mind that at times the sound is a bit coarse, or that all attacks and releases are not perfect. What counts is the message, and in this case, there is no doubt of the value and artistry of the message.

These recordings were made in the 50’s and 60’s with the Philharmonia Orchestra in London. Record producer and artistic director Walter Legge formed the Philharmonia after World War II for the purpose of recording the orchestral masterworks under ideal conditions with some of the world’s greatest conductors. And that he did. At first, the Philharmonia served as the main venue for a promising young German named Herbert von Karajan, and soon after that expanded to other notable maestros and soloists.

The Philharmonia continues today, not only as a recording orchestra, but also giving live concerts in London and elsewhere. It is one of London’s five major orchestras. In the 1990’s, I had the pleasure of conducting the Philharmonia in two separate orchestral albums. And what a pleasure that was! Their work ethic, ability to absorb and interpret difficult music very rapidly, tone quality, dedication, artistry, and discipline left a strong impression with me.

Back to Otto Klemperer. This is what William Mann wrote in 1985:

“It was a supreme interpreter of the German Classical masterpieces, from Haydn to Richard Strauss, that concert audiences chiefly admired Otto Klemperer. In the years between 1951 and his retirement in 1972 is when most of his

|

|

records belong. In Beethoven, particularly, he offered a granite-like orchestral sonority and objectivity in his balance of form and content that contrasted refreshingly with the styles of such idolized conductors as Furtwangler, Bruno Walter, and even Toscanini. Under Klemperer, the greatest Beethoven sounded more truthful and honest, and even more grand and inspiring.” records belong. In Beethoven, particularly, he offered a granite-like orchestral sonority and objectivity in his balance of form and content that contrasted refreshingly with the styles of such idolized conductors as Furtwangler, Bruno Walter, and even Toscanini. Under Klemperer, the greatest Beethoven sounded more truthful and honest, and even more grand and inspiring.”

I was especially astounded (again) at the energy level of the music, whether it was loud or soft. The forward momentum, the commitment, the impact, and the communication, which is sometimes quite difficult to convey in a recording versus a live concert, manifests itself at all times. It’s all there. Many live interpretations today by various conductors and orchestras may be faster, louder, even more precise; and less perceptive audiences stand up and cheer. But this isn’t really what serious music is all about.

Klemperer started his career in Germany, and, curiously, in his early years he was also known as a champion of the modern music of his time. Because of his Jewishness, he left Germany and remained in England and the Americas. His last twenty years of life were full of health problems, but, miraculously, he recovered time after time. Many of his last recordings were conducted from a wheelchair.

Several of the older musicians of the Philharmonia talked to me about the recording sessions with Klemperer. They told of wonderful times of deep and inspiring music making. I cherish those stories.

Two other Klemperer family members are worth mentioning. His son, Werner was a famous actor; he is best remembered by his role of the fumbling Nazi officer in the television comedy Hogan’s Heroes. Maybe the concept of such a show is and was in bad taste for many of us, but his acting was always admirable. He was also a serious stage actor and a pianist, and in the 1980’s we saw him as an actor in Broadway. His daughter, Erika, was a violin student at Indiana University in the early 1970’s while I was there working on my doctorate studies in conducting.

Just to charge your aesthetic and artistic batteries, and to put what we hear nowadays in perspective, pull out your old LPs, or purchase the re-issues in compact discs of the Beethoven-Klemperer-Philharmonia combination. Or listen to them on XLNC1, 104.9 FM radio, which plays these historic recordings frequently. I promise that the experience will be revealing!

|

|