|

By Donald H. Harrison

YORBA LINDA, California—The Richard Nixon Presidential Library and Museum complex is also Richard Nixon’s birthplace and grave site—in short, a place where one may review the entire scope of his life, weighing his accomplishments against his misdeeds. YORBA LINDA, California—The Richard Nixon Presidential Library and Museum complex is also Richard Nixon’s birthplace and grave site—in short, a place where one may review the entire scope of his life, weighing his accomplishments against his misdeeds.

Although the format is much different, the experience is in some ways quite similar to seeing Sammy, the musical retrospective (now playing at the Old Globe Theatre in San Diego) that leads viewers through the high and low points of entertainer Sammy Davis Jr.’s life.

If you’d like to preview the plot, read the Wikipedia entry about Sammy Davis Jr., which is remarkably parallel to songwriter and playwright Leslie Bricusse’s script, though the latter sometimes compresses the timeline for dramatic effect.

The lives of Nixon and Davis famously intersected on two occasions within a year of each other. Davis was among the entertainers who appeared at a concert in 1972 in Miami Beach supporting President Nixon’s reelection campaign, and, when Nixon came on the stage unannounced, Davis gave him a hug—much to the distress of many of his liberal show business colleagues.

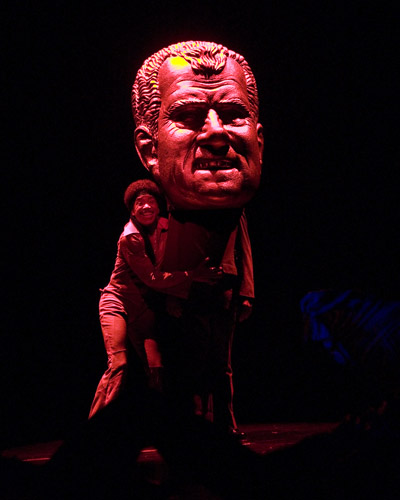

Here’s a link to an Associated Press photo of that hug; above right is an Old Globe photo from its Sammy production in which actor Obba Babatunde, who portrays Davis, hugs a larger than life figure of the controversial president.

In 1973, Davis was a guest at Nixon’s White House, the historical speculation being that he was the first African-American to ever sleep in the residential quarters of the President’s home.

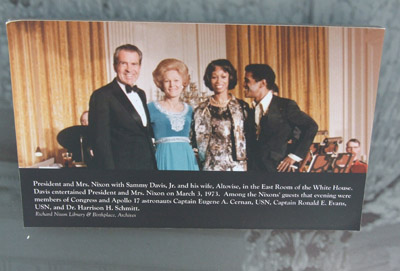

The museum displays in its lobby a photograph (above) of Richard and Pat Nixon and Sammy and third wife Altovise Davis in 1973. Unfortunately, neither the museum nor the play probe the dynamics of the Nixon-Davis relationship, but the May 17, 1990, New York Times obituary of Davis may provide a telling clue to both men’s motivations.

Twelve years before he slept in the Queen’s Bedroom at the White House, Sammy Davis Jr. had been scheduled to participate in the 1961 inauguration of Nixon’s arch-rival, President John F. Kennedy, but the invitation was revoked after he married his second wife, Swedish actress May Britt—the Kennedys fearing that giving Davis a political embrace so soon after his inter-racial marriage would anger Southern Democrats whose support he needed to pass his programs. At the time, interracial marriages were forbidden in 37 states.

(Incidentally, the marriage in California to Britt came after Davis lost one eye in a traffic accident. While hospitalized, the entertainer began studying Judaism—ultimately to convert—prompted by a conversation he had with vaudevillian Eddie Cantor about the similarities between the Jewish and African-American experiences. Many readers of the San Diego Jewish Press-Heritage, of which this publication is in many ways a successor, were familiar with the late columnist Rabbi Will Kramer, who officiated at the controversial Davis-Britt wedding).

Later in his life, Davis said he regretted his support for Nixon, explaining that he felt that Nixon had not lived up to his promise

to work for Civil Rights legislation. The Kennedy family subsequently made amends to Davis Jr., sponsoring a Kennedy Center salute to his career as a showman.

Prior to such revisionism, however, for both Nixon and Davis, the Kennedy family may well have represented wealth and privilege, which stood in contrast to their own humble beginnings. Davis, who was three or four years old (accounts vary) when he left Harlem to go on stage with his father as part

Go to the top of next column

|

|

of the Will Mastin Trio, never had any formal schooling, and grew up understanding that his success and that of his family depended upon the applause of others.

Nixon was born in the small bedroom off the combination living room-dining room in a store-bought home that his father assembled from a kit. Here he learned to play a piano and several other musical instruments before the family eventually moved to Whittier, California.

Whereas Davis tried to please everyone, Nixon was a successful debater at Whittier College who came to consider public life as a contest in which one had to choose sides and enemies. After returning home from World War II, he became a Republican candidate for Congress, defeating Jerry Voorhis, and entering the same freshman congressional class as Jack Kennedy. Like Kennedy also, he soon stepped up to the U.S. Senate, defeating liberal Democrat Helen Gahagan Douglas. Nixon was known as a fierce anti-Communist, one who, in the view of opponents, would smear anyone to work his way up the political ladder.

Along the way to the top of their respective professions, both men got beat up – Davis, physically, when white racist soldiers roughed him up after performing with white actresses in military stage shows, and Nixon, politically, in his losses in 1960 for President to John F. Kennedy and in 1962 for California governor to Edmund G. Brown Sr.

Both men, too, had people who despised them, purely and simply. Davis found he was hated on both sides of the racial divide—by whites who feared the blurring of racial lines, and by blacks who thought his marriage to Britt meant he had deserted them.

One can conclude that Davis and Nixon both had deep inferiority complexes, notwithstanding their many accomplishments. Nixon’s paranoia about his enemies led to his participation in the cover-up of the Watergate burglaries and ultimately to his disgrace as the first (and only) president to be forced to resign from office. Davis’s lack of an emotional anchor—he had adopted Judaism in theory but not in the sense of committed practice—led him to multi-million dollar spending sprees, numerous extramarital affairs and to illegal drug use.

Despite their flaws, both men achieved remarkable heights and helped to personify their era. The Nixon Library and Museum and Sammy are equally worth seeing.

|

|